There was already a Hammond organ in his father’s club, and it seemed to be just waiting for him.

By the age of sixteen, Larry Young was accompanying blues shouters and gritty hard-bop saxophonists. After all, that was exactly what the Hammond organ seemed made for: funky, soulful music. Jimmy Smith had been the first to demonstrate it, and a whole generation of organists – all the “Brother Jacks” and “Big Johns” – followed in his footsteps. But Larry Young knew early on: “I’m going my own way. I want to be myself.” The bluesy licks, soulful vamps, and wailing effects just weren’t enough for him. He dug deeper and uncovered entirely new beauties in the Hammond organ: precise lines, dark tonal colors, extended forms, wide dynamic range, and unexpected structures. In 1967, critic A.B. Spellman called him the “only serious modern organist.”

His role model wasn’t some blues honker, but rather the scale explorer John Coltrane. At the time, no other organist could – or wanted to – take the path Coltrane had paved, from the hyper-complex to the modal, into the ecstatic and spiritual. Larry Young jammed with John Coltrane and later with Jimi Hendrix. Around 1970, he played with the “electric” Miles Davis and with Carlos Santana. With John McLaughlin, he joined Tony Williams’ Lifetime, the first electric fusion band. His liberation of the Hammond organ laid the foundation for psychedelic jazz and the rock organists of the 1970s.

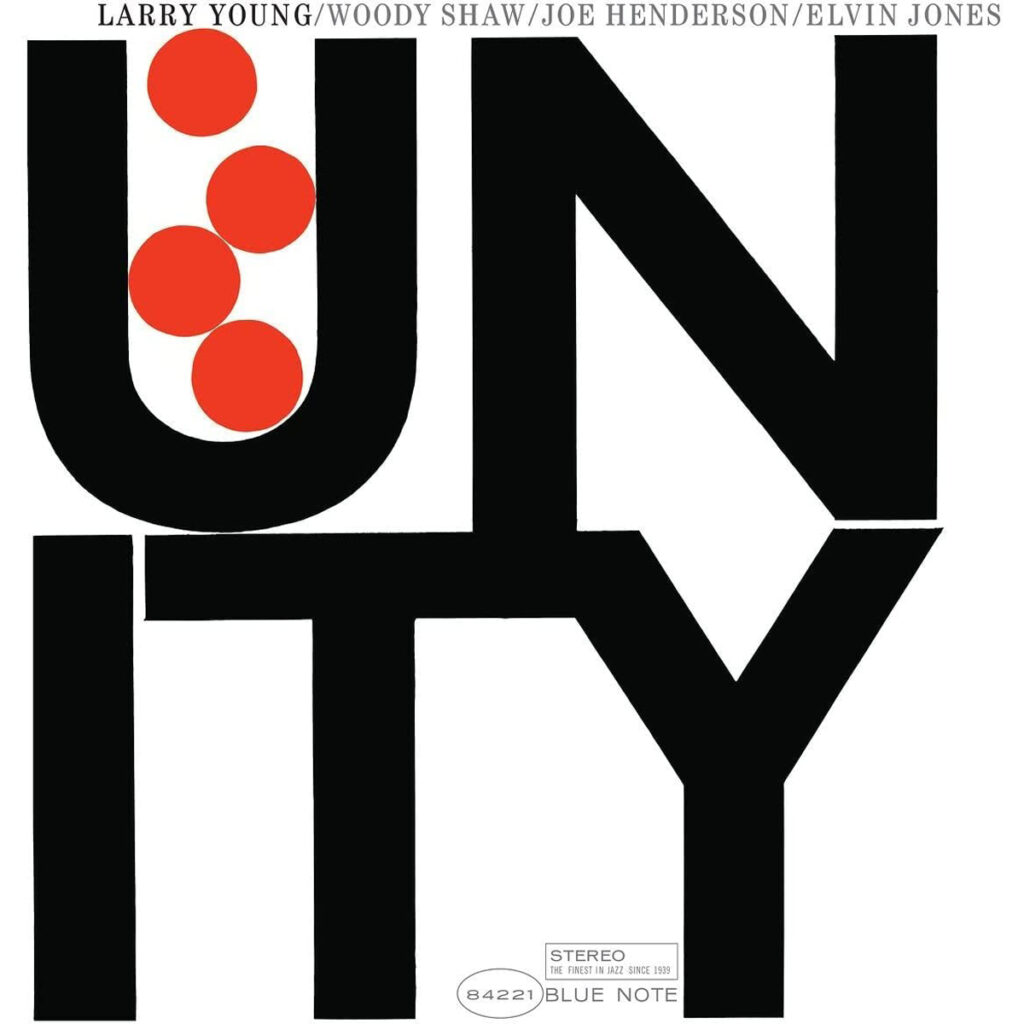

Unity was the most important milestone on Larry Young’s journey. While much of the young jazz scene in 1965 was drifting into completely free playing (Coltrane himself was taking his final step in that direction), Larry Young held his course: largely modal but tonally unbound, with clear structures and swinging like mad.

For this, he borrowed the magnificent horn section from Horace Silver and Coltrane’s miracle drummer. Joe Henderson on tenor saxophone and 20-year-old firebrand Woody Shaw on trumpet spark an almost unparalleled blaze. Elvin Jones, whose polyrhythms dance across the drums, gives the swing a new kind of freedom. Joe Henderson’s “If” is a rugged, wild theme that still functions like a blues. Woody Shaw contributes three brilliant compositions that experiment with modality and harmony. “The Moontrane” is dedicated to Coltrane, while “Zoltan” is dedicated to Hungarian composer Zoltán Kodály. It begins with a march theme from Kodály’s Háry János Suite, which became the inspiration for Shaw’s melody.

In this sonic world, you wouldn’t necessarily expect a Hammond organ. But there it is: pianistically precise and saxophonelike in its freedom, igniting harmonies, modes, bass lines, and rhythms, shaping the flow, clarifying the texture. “Larry listens to you and complements you,” said Joe Henderson. And whenever Larry Young takes a solo here, it turns into a highly complex, virtuosic, breathtaking duo with Elvin Jones on drums. The two play Thelonious Monk’s “Monk’s Dream” together as a duet – a small jewel. Larry Young sensed right away that this band was something special: “Everything just fit together” – which is why he called the album Unity. Critic Nat Hentoff wrote: “I have rarely heard an album with such consistent, collective spirit.” The Penguin Guide to Jazz puts it simply: “Quite simply a masterpiece.”

Find Unity by Larry Young on discogs.com