As one of the first musical art forms created in the US to attain worldwide acclaim and acceptance, jazz straddles the line between the challengingly cerebral harmonic complexity found in orchestral classical music and the interactively creative spontaneity of NBA-caliber basketball.

Capturing Jazz Lightning In a Bottle – Recording With Trumpeter Franco Ambrosetti was originally published in Copper Magazine Issue 203

FIDELITY cooperation with Copper Magazine.

Read this article also in Copper.

Jazz recorded in the studio, however, may take advantage of technology’s ability to edit, replace, and otherwise manipulate performances after the fact, not unlike in pop, rock, R&B, hip-hop, and other music genres.

No stranger to the readers of Copper, celebrated engineer and producer Jim Anderson (13 Grammy Award album wins and 26 nominations) graciously invited me to observe a recording session he was engineering for composer and trumpeter Franco Ambrosetti (pictured in the header image) at Sear Sound in New York City.

Hailing from Lugano, Switzerland, Franco Ambrosetti is the son of European bebop pioneer Flavio Ambrosetti, and has been a fixture on the international jazz scene since 1967. He has recorded 26 albums to date as a bandleader, with guest appearances on another 50 more with friends such as Michael Brecker, Tommy Flanagan, Greg Osby, Gato Barbieri, John Abercrombie, Kenny Barron, Italian singer MINA, and many others.

Jeff Levenson, who has produced and/or supervised two Grammy award-winning and 11 nominated albums, was in the producer’s chair. Steven Sacco assisted Jim and ran the Pro Tools digital audio workstation (at 24-bit/192 kHz).

The musicians whom Franco and Jeff rostered for this session included: Peter Erskine on drums, John Scofield on electric guitar, bassist Scott Colley, pianist/music director Alan Broadbent, and Franco himself on flugelhorn and trumpet.

Jim explained that the first composition to be recorded was an Ambrosetti original entitled “Habanera.” Franco went on to note that the song’s original use was for a theater production, and that a subsequent session would add orchestral strings, brass, reeds and percussion. As a result, Alan Broadbent was tasked with the challenge of maintaining the tightrope walk for the musicians between playing too sparsely and mindful of the string overdubs to follow, and maintaining the creative lightning in a bottle magic that occurs when top-notch musicians can stretch out and play freely together, throwing musical phrases back and forth into all types of emotionally-laden moments.

Interestingly, Levenson had notes on areas of the piece regarding things that had been planned for the composition on his laptop computer, but Jim Anderson did double duty as both recording engineer and score tracker, i.e., keeping reference to where in the sheet music score they were in “Habanera” so that Levenson could refer back to a specific measure, which would allow the musicians to punch in or re-record from a particular phrase or passage if needed.

In keeping with the basketball analogy, Jeff Levenson’s role was that of the head coach, Jim Anderson’s was equivalent to the offensive coordinator, Alan Broadbent served as the point guard, while Franco was the first option shooter.

Keeping in mind the strings and other instruments that would be added to “Habanera” in a subsequent session, the piece brought to mind elements of Ambrosetti’s previous works, particularly “Nora’s Theme” from Nora (2022), his previous record. It was also cut at Sear Sound with Jim, Jeff, and the same band, except with Alan wearing two hats as both conductor (for the orchestral overdubs later on) later on, as well as pianist for this session.

The use of flugelhorn as a lead instrument with strings and a sparse, jazz rhythm section playing over simple melodies that contain harmonically complex voicings are reminiscent of the soundtrack pieces and hit songs of Burt Bacharach, and “Habanera” had a similar early 1970s feel. It was easy to picture what it would sound like, once punctuated by the strings to be added.

Although Jim Anderson mixed Nora at his private New York studio, he informed me that he planned to do an immersive mix for the new Ambrosetti project at SkywalkerSound in California.

After several takes and alternate sections to be comped and edited later during the mixing stage, the band took a break and then returned to record an arrangement of Mal Waldron’s “Soul Eyes.”

With apparently less restraints for what they needed to edit in their playing, all of the musicians were noticeably more relaxed as they launched into “Soul Eyes” – resulting in a looser performance with more abandon and swagger. The solos taken by this gathering of jazz veterans were a delight to witness, and the fun they took in one another’s playing was palpable.

After several takes, the band broke for a late afternoon lunch and to also listen to the playback. Jim introduced me to the musicians, where I got to chat briefly with John Scofield and more in-depth with Franco Ambrosetti.

Scofield exclaimed to me that he had to consciously self-edit his playing and play more restrained in anticipation of the string and brass arrangements. He chuckled about playing “a musical skeleton” of the guitar part instead of what he might normally play if the music was to be solely heard as played by the quintet in the room. While certainly much leaner than his solo recordings or covers of blues and Grateful Dead tunes, Scofield’s approach recalled Miles Davis’ focused trumpet lines on Kind of Blue.

Franco Ambrosetti’s perspective on composing music reflected a strong preference for structure and cues, not unlike what can be found in classical music. His extensive experience in composing original music for theater productions and film soundtracks bear this out. In addition to the theater origins of “Habanera,” Ambrosetti has also composed the soundtracks for feature films like the Swiss-German World War II drama The Journey (1986), the Italian-Swiss film Terra bruciata (1995), and for documentaries and TV series. As a result, Ambrosetti’s original music melds the moods, rhythms, and harmonic sophistication of jazz with melodic themes and orchestral arrangements from the Western European classical music tradition.

As a musician and native New Yorker, I have had the good fortune to have been able to either visit or do recording work in some of the best studios in the world. However, Sear Sound was one that I had never entered before, so this session was of special interest to me.

Founded by the late Walter Sear in the 1960s, Sear Sound is the oldest professional New York recording studio still in operation. A New York landmark, Sear Sound is well-known for its collection of vintage analog tube gear and for the many great artists who have recorded there, such as David Bowie, Steely Dan, Lou Reed, Lenny Kravitz, Nora Jones, Wayne Shorter…and the list goes on.

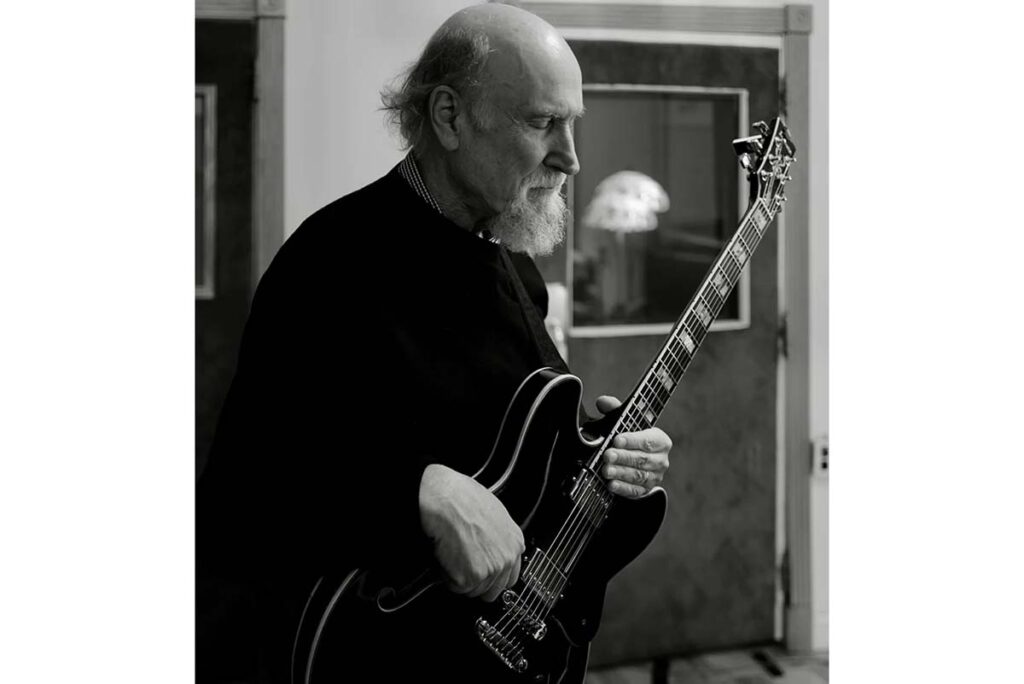

Jim Anderson took time during the break to walk me through Studio C, where I got to see which microphones he had chosen along with their placements (a mix of predominantly Sanken mics with Neumann U87s to capture the ambient room sound).

Jim also showed me the custom Sear-Avalon 60 x 24 x 2 console with flying faders (volume sliders that can operate automatically, making it easier to do a mix), the multiple racks of Pultec, UREI, Teletronix, and other equalizers and processors, and some customized Millennia Media and John Hardy M-1 preamp units that Jim opted to bring from his personal studio for these sessions.

As the playback through the Genelec 1031A monitors filled the room, the musicians grinned from ear to ear, pleased with the results of their handiwork. Jeff Levenson took notes on things he wanted to do in post-production and although I was invited to stay for additional recording, I took my leave, impressed with what I had witnessed and heard.

I think the most surprising aspect to the session was how conventional it was, especially when compared to most other rock, pop, R&B, or even hip-hop sessions. I had expected a session where once the mics were set up and the Pro Tools record button was hit, the players would just let it rip, as they did in Jim Anderson’s recent Donald Vega project, As I Travel.

I was unprepared for a jazz session with multiple punch-ins, where iconic players on the caliber of a Peter Erskine or John Scofield might actually flub a part, and even passages with alternate takes had to be comped and edited during mixdown.

On the other hand, it was refreshing to once again be in a large-enough professional recording studio where all of the musicians could play together in the same space. There’s a magic that happens when world-class musicians interact with each other and spontaneously create music that is far different from when individual musicians overdub their parts in isolation, which has, for better or worse, become the norm for much of today’s record production.

It was certainly a treat to sit in and observe the Ambrosetti sessions at Sear Sound, and I am grateful to Jim, Jeff and Franco for welcoming me into their private world for a few hours to hear them capture jazz lightning in a bottle.

All images courtesy of Jim Anderson.

Special Thanks to Copper Magazine