Progressive rock entails tempo changes, classical and jazz reminiscences, extensive instrumental parts and surprising instruments. Because all of this is hard to fit into a three-minute song, there is the long track.

When it comes to long tracks, King Crimson offers an abundance of choices. By far their longest piece was created in 1970, at a time when the band strictly speaking didn’t actually exist at all. In September, Robert Fripp gathered several musicians in the studio and gave them precise instructions. For the first time, he assumed sole responsibility for the music – Lizard, the ambitious album, was meant to be his personal breakout coup. (Only lyricist Peter Sinfield still had a small say.) At the time, Fripp was especially interested in the jazz sextet of pianist Keith Tippett, whom he would have liked to integrate fully into the band. In the end, at least three Tippett musicians took part in the album.

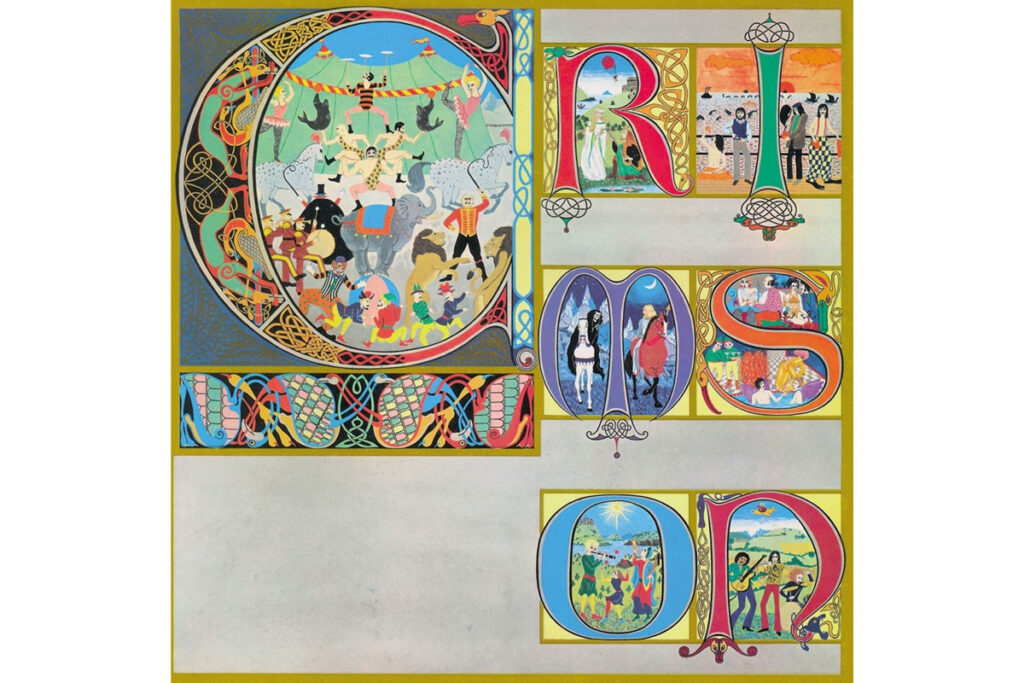

The 23-minute title track “Lizard” fills the entire B side of the original LP. Essentially, it is a suite consisting of four very different movements, each with its own title. The third movement is further subdivided into three (also titled) sections. Through the various titles and the lyrics, the name of a certain Prince Rupert – a legendary figure in English history (17th century) – keeps appearing. The repeated references to glass (glass tears) also relate to him, specifically to the so-called “Prince Rupert’s tears” (also known as Bologna tears), a special type of glass ornament. The historical setting of the piece then gradually drifts toward the Middle Ages (dragon, peacock, swan). The beautiful album cover, with its ornamental lettering, is likewise inspired by medieval art. Those who look closely will find portraits of the Beatles and other rock heroes hidden in the small illustrations.

The suite contains two vocal song sections. The first (“Prince Rupert Awakes”), featuring guest singer Jon Anderson (Yes), forms the opening movement. This ballad (0:00–4:34) is comparable to earlier Crimson song melodies such as “In the Court of the Crimson King” or “Epitaph” – you could easily picture Greg Lake as the singer as well. Each verse is accompanied more richly than the last, with the third even becoming partly dissonant. At the end, there is an almost “symphonic” build-up with wordless vocals, Mellotron, Tchaikovsky-style piano – and already mixed in is the bolero rhythm of the second movement (“Bolero – The Peacock’s Tale”). Here, the horns take center stage: Mel Collins on alto sax, the classically trained oboist Robin Miller, and Keith Tippett’s colleagues Mark Charig and Nick Evans on cornet and trombone. (Tippett himself sets the directional changes at the piano.) This movement (4:34–11:07) begins in a pseudo-classical manner with a Spanish-tinged cornet theme. (“Lizard” is also an old name for the cornet.) Later, it turns into a slightly bluesy Dixieland passage (from 7:07), which briefly intensifies into free jazz.

The third movement (“The Battle of Glass Tears”) depicts a knightly battle. The gentle first part (“Dawn Song”) is the second vocal section of the suite (11:07–13:26), sung by Gordon Haskell and introduced by the English horn. In the magnificently intense second part (“Last Skirmish,” 13:26–19:35), the restrained free-jazz horns erupt once more, further embellished with rocking baritone sax riffs, a flute improvisation, abundant Mellotron, a subtle interplay between bass and guitar, and more. In part three (“Prince Rupert’s Lament,” 19:35–22:08), Fripp’s imaginative electric guitar provides a melancholic, legato conclusion. The anarchic waltz miniature “Big Top” (22:08–23:15) brings the suite to an end. For music critic Richard Williams, Lizard was proof “that rock can compete with classical music.”

Find King Crimson – Lizard on www.discogs.com