An unexpected reunion amid political surveillance, pianistic genius, and personal truth.

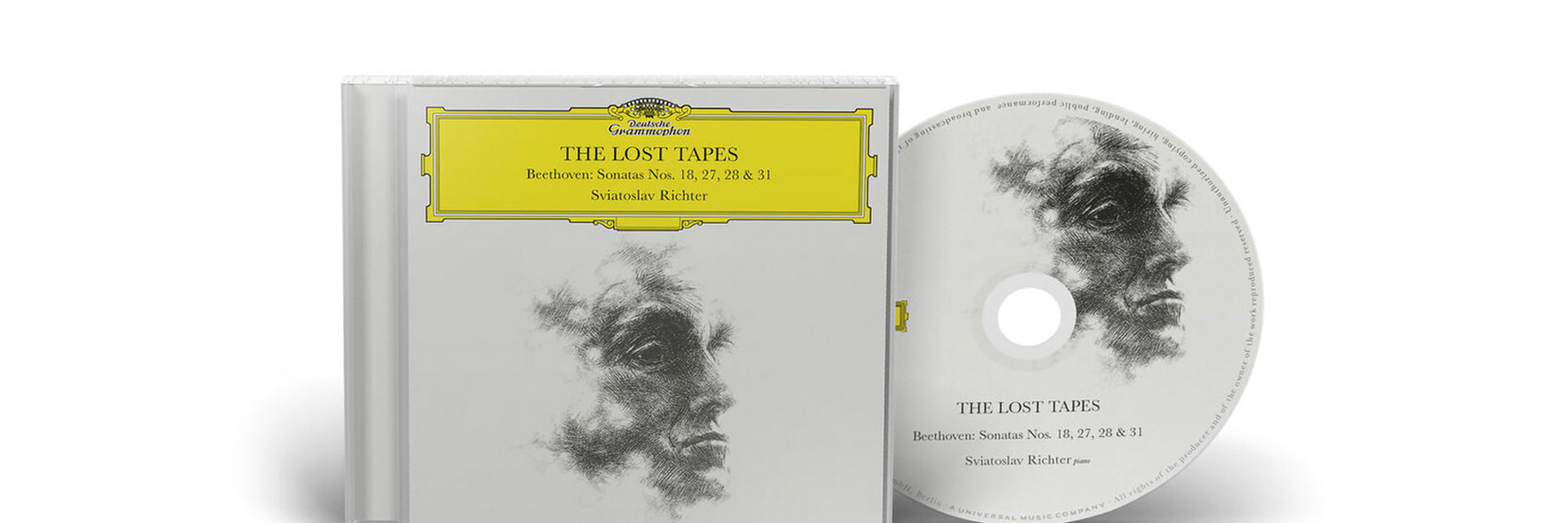

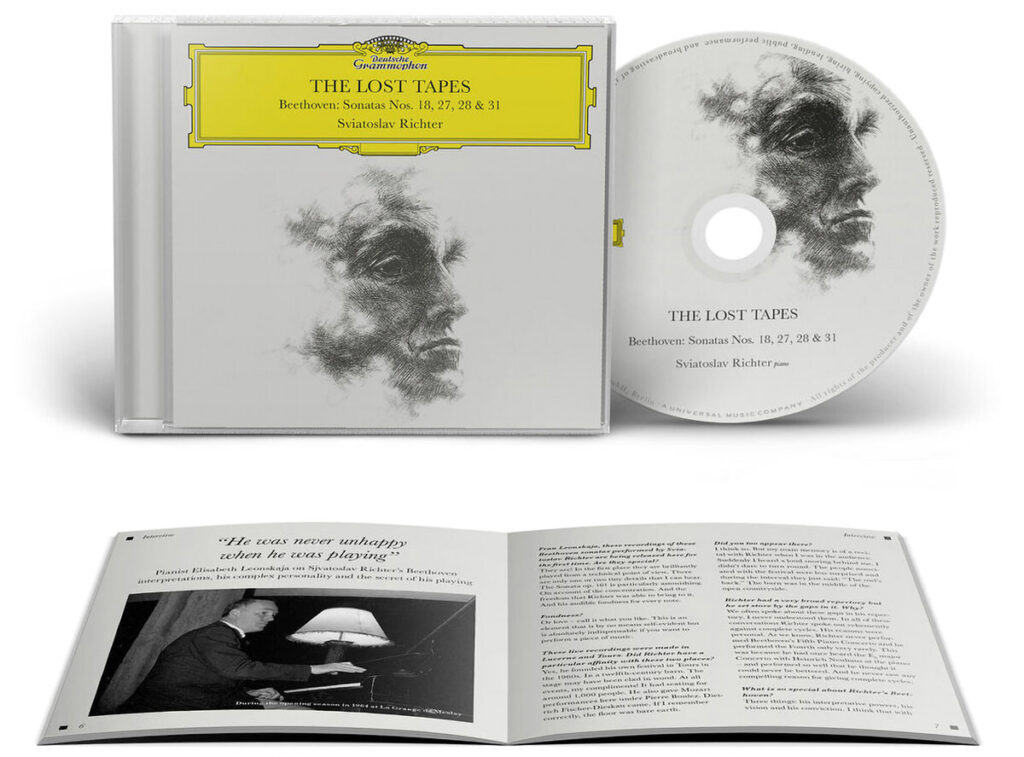

Sviatoslav Richter – a name that inspires awe among connoisseurs, yet for many exists only as a legendary, almost mythical figure at the margins of our collective musical memory. The newly released Deutsche Grammophon edition The Lost Tapes brings us closer to the man than biographical sketches or iconic images ever have. These recordings from Lucerne and Meslay, taped in 1965 and never before officially released, are a monumental stroke of luck – musically as well as historically.

Born in 1915 in Zhytomyr, Richter grew up bilingual (German and Russian) in Odessa. His true pianistic maturation did not begin until age 22 at the Moscow Conservatory, under Heinrich Neuhaus – who recognized in him a “genius” to whom he “could hardly teach anything more.” But Richter’s life was no straightforward artist’s fairy tale. His father was executed by Stalin’s henchmen in 1941 as an alleged spy. From then on, as a member of the ethnic German minority, Richter lived at the tense intersection of political surveillance, identity conflict, and musical excellence. Not until 1960 – after interventions by major colleagues like Gilels, Oistrakh, and Rostropovich – was he allowed to travel to the West for the first time.

Richter’s relationship with the public was ambivalent. He was no narcissist chasing applause, but a radically work-focused musician. This attitude runs like a red thread through the rediscovered recordings. Everything is directed toward Beethoven – toward the truth of the music, not its glamorous packaging. In his hands, the Sonatas No. 28 in A major, Op. 101, and No. 31 in A-flat major, Op. 110, unfold as uncompromising inner landscapes. The fugue in the Allegro ma non troppo of Op. 110, in particular, bursts beyond any notion of mere fidelity to the text through Richter’s tonal edge and controlled emotional intensity: classicism without coldness, passion without posturing.

It is telling that in an interview, Richter criticized none other than Glenn Gould – Canada’s anti-star – saying, “He doesn’t love enough.” That hit home. At his Moscow recital in 1957, Gould played the Goldberg Variations without repeats – for Richter, a sacrilege. For him, repeats were not a formality but moments of transformation: “The first time strict, on the repeat I step outside myself.” In The Lost Tapes, Richter’s Beethoven emerges as a countermodel to any sort of mechanistic “textual fidelity.” He balances clarity with wildness, structure with sheer sonic intoxication. The Allegro of the Op. 101 Sonata resembles a controlled dive, a frenzy that – thanks to its rhythmic precision – never collapses into chaos.

Even so, there is a point that unites him with Glenn Gould: both were obsessed with perfection in their recordings. Richter repeatedly demanded retouching of passages he considered flawed – something far harder to accomplish in live recordings than in Gould’s manic studio sessions.

Why, then, did these tapes disappear into obscurity for decades? No one knows. Was it the “metallic” sound of the Lucerne concert grand, as Markus Kettner suggests? Political reasons? Or simply the lack of interest on the part of Soviet authorities in releasing a recording that did not fit the narrative of “cultural export”? For decades, these performances existed only as internal test pressings. Yet Elisabeth Leonskaja, Richter’s longtime companion, emphatically rejects the idea that the tapes were withheld for artistic reasons. She describes Richter on these recordings as “visionary,” someone who deliberately pushed beyond his own fixed interpretive concepts through expressive intensity – always within the score, yet always with personal courage to diverge.

Richter’s life was shaped not only by musical decisions but by political constraints. When he performed in Lucerne in 1965, he was surrounded by Soviet secret service agents – a silent but ever-present corset. It is easy to believe that music became a space of escape for Richter; at least the rediscovered recordings allow for such an interpretation. At the same time, he created a stage of his own outside the official cultural apparatus: the Grange de Meslay, a medieval barn near Tours that he had converted into a concert space in 1964, became the home of his private festival.

This album shows Richter at his zenith – technically brilliant, expressively unbounded, inwardly alert. He plays Beethoven not as a monument but as a living contemporary urgency. No wonder he avoided the grandiose Fifth Piano Concerto throughout his life – he felt closer to the intimate, almost speaking Beethoven than to the heroic one. And although Richter was often his own harshest critic (“Whenever I was satisfied, no microphone was on”), The Lost Tapes contradicts these self-doubts in breathtaking fashion.

The album is available on CD and as a double vinyl release. It is accompanied by essays by Kai Luehrs-Kaiser, Markus Kettner, and Jed Distler – essential reading for anyone hoping to approach the complex universe of this pianist. The Lost Tapes is not merely the rediscovery of some arbitrary concert, but a window into the soul of a man who didn’t play music so much as live it.

These recordings are uncompromising, intense, and – above all – authentically honest. They reveal a pianist who never sought to please – and who remains unforgettable precisely for that reason. Anyone who has known Richter only as a name now has the chance to truly encounter him: in his contradictions, and thus in his truth.

Ludwig van Beethoven – Piano Sonatas Nos. 18, 27, 28, 31

Sviatoslav Richter

Label: Deutsche Grammophon

Format: CD, Double LP, DL 24/48