In an art form driven by tempo, virtuosity, and expressiveness, Mal Waldron was a quiet exception.

Born in 1925 in New York, raised in Queens, the child of West Indian immigrants – Mal Waldron could easily have become someone else. His parents wanted nothing to do with jazz and encouraged a classical education. But Waldron listened to swing on the radio and discovered jazz for himself – first on the alto saxophone, inspired by Coleman Hawkins. Later he switched to piano, partly out of pragmatism: Charlie Parker’s speed seemed unreachable, and Waldron felt he didn’t have the ego required for a horn. The piano was more intimate, more controlled. After studying at Queens College, Waldron began his career as a pianist in the New York scene in the early 1950s. He played with Charles Mingus and Jackie McLean. His time with Mingus was especially formative – not just musically. At the time, Waldron was still a disciple of Horace Silver and Bud Powell, his playing full of passing tones, harmonic richness, and runs. Mingus pushed him toward clarity, toward reduction. That call for precision – both harmonic and emotional – would remain a guiding principle in his playing.

The turning point came in 1963. A heroin overdose led to a complete breakdown. Waldron couldn’t remember anything – not music, not even his own name. He trembled and was unable to play. Shock treatments, lumbar punctures. A reset. What followed was a painstaking recovery: first listening to his own recordings, then playing simple lines, writing down solos, until improvisation became possible again. This process took years – and it fundamentally changed his playing. Before the collapse, Waldron had been a lyrical player. Afterward, he became more angular, stripped-down, raw; he made repetition the center of his expression. Where others got lost in chord changes and melodic variations, he stubbornly stuck with a motif, altered it slightly, let it sit, turned it, repeated it – economical, focused, attentive to the essential.

After the breakdown, Waldron no longer found a place in the U.S. In 1965 he moved to Europe – first to Paris, then Rome, Cologne, finally Munich and Brussels. The decision came easily; he already knew Europe from touring. In interviews, he later spoke of the “competition terror” in the U.S., and of his frustration that Black musicians were paid less than their white colleagues. In Europe, he could work – independently and with respect. Record labels also appreciated his work. Free At Last was released in 1969 as the first album on the label ECM, which had not yet risen to fame back then. In 1971 came The Call as the first album on the sublabel JAPO – featuring electric piano, then still unusual for Waldron. Later, he also played with the Krautrock band Embryo, remaining experimental but always true to himself. Japan became his second home during the 1970s and 1980s. He was revered there, touring regularly and recording many albums. Waldron spoke four languages: English, French, German, and Japanese. He was international, but never generic. In the 1990s, he moved to Brussels, where he stayed until his death in 2002. In Belgium, he said, people paid more attention to cars than to traffic lights – he liked that. He rarely performed in the U.S. again; the smoking bans in clubs annoyed him. Until the end, he remained stubborn, singular, uncompromising.

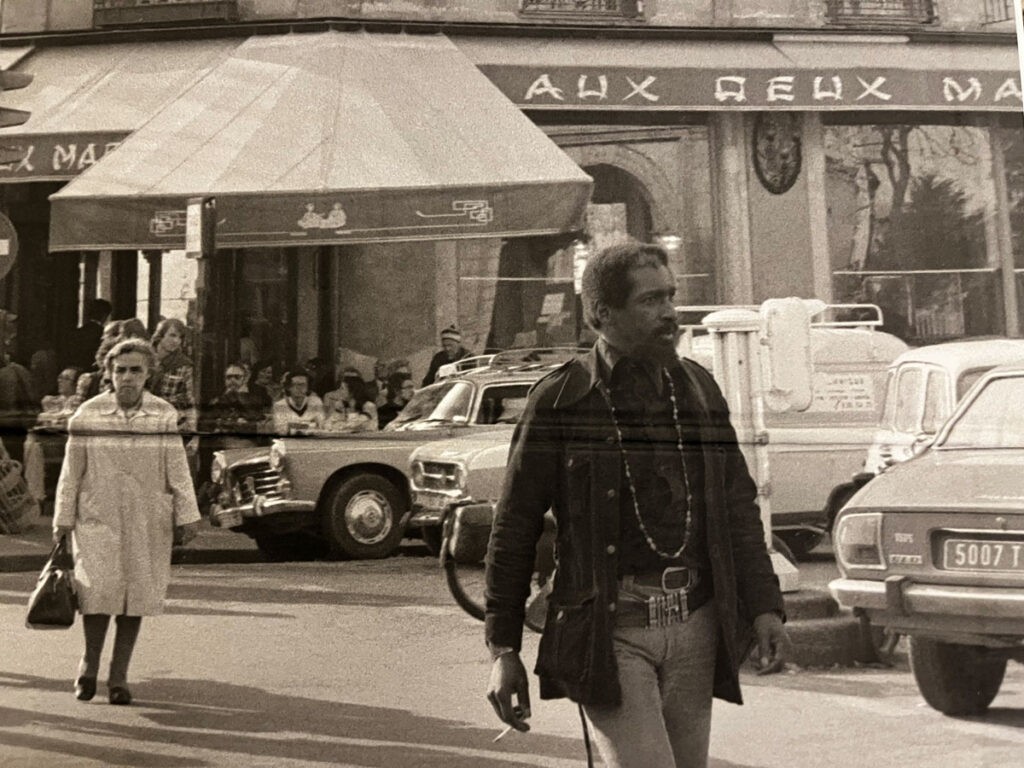

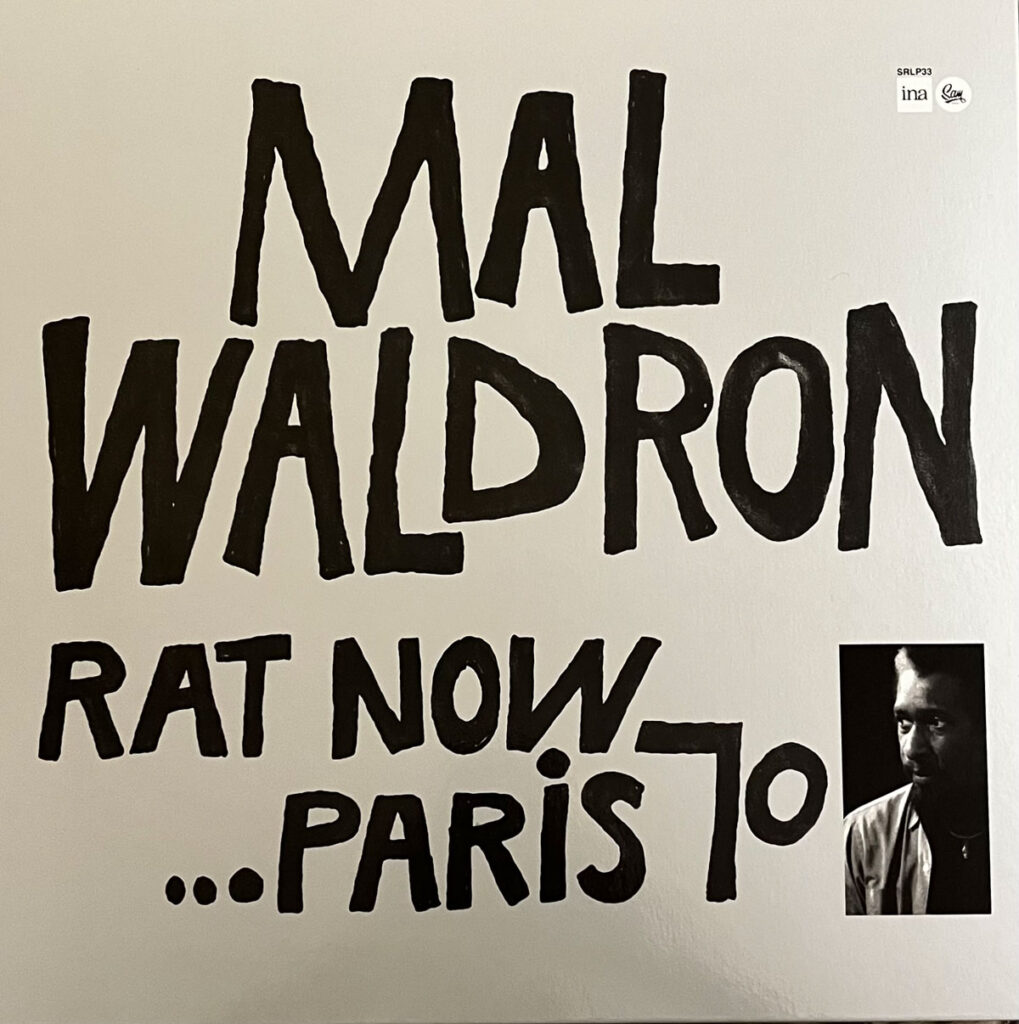

Mal Waldron Trio – Paris 1970

A previously unreleased live recording of the Mal Waldron Trio from March 10, 1970, recorded at the Hotel Palais d’Orsay in Paris as part of the International Sound Festival and broadcast on André Francis’s Jazz Vivant radio show, is now being presented by the label Sam Records – which we have already praised here in the Vinyl Corner for its loving reconstruction of jazz recordings made in France. Waldron appears here with a young, electrifying Christian Vander on drums and bassist Jean-François Catoire. The trio had already caused a stir in Antibes in the summer of 1969 – here now is the continuation, even more intense, even more mature. The concert recording captures Waldron in a creative transition: after years of personal crisis and retreat to Europe, he returned to his playing with new clarity and density. His left hand drives relentlessly forward while the right builds controlled tension – minimalist, focused, yet full of expression. Vander plays impetuously, raw, free – a perfect complement to Waldron’s structured depth. Catoire anchors it all with calm intensity, yet can also sound highly expressive, even downright abrasive when bowing the bass. As always with Sam Records, the release impresses with a pristine pressing, high-quality cover, and audiophile mixing – a complete package reaffirming the special standing of the small French label.

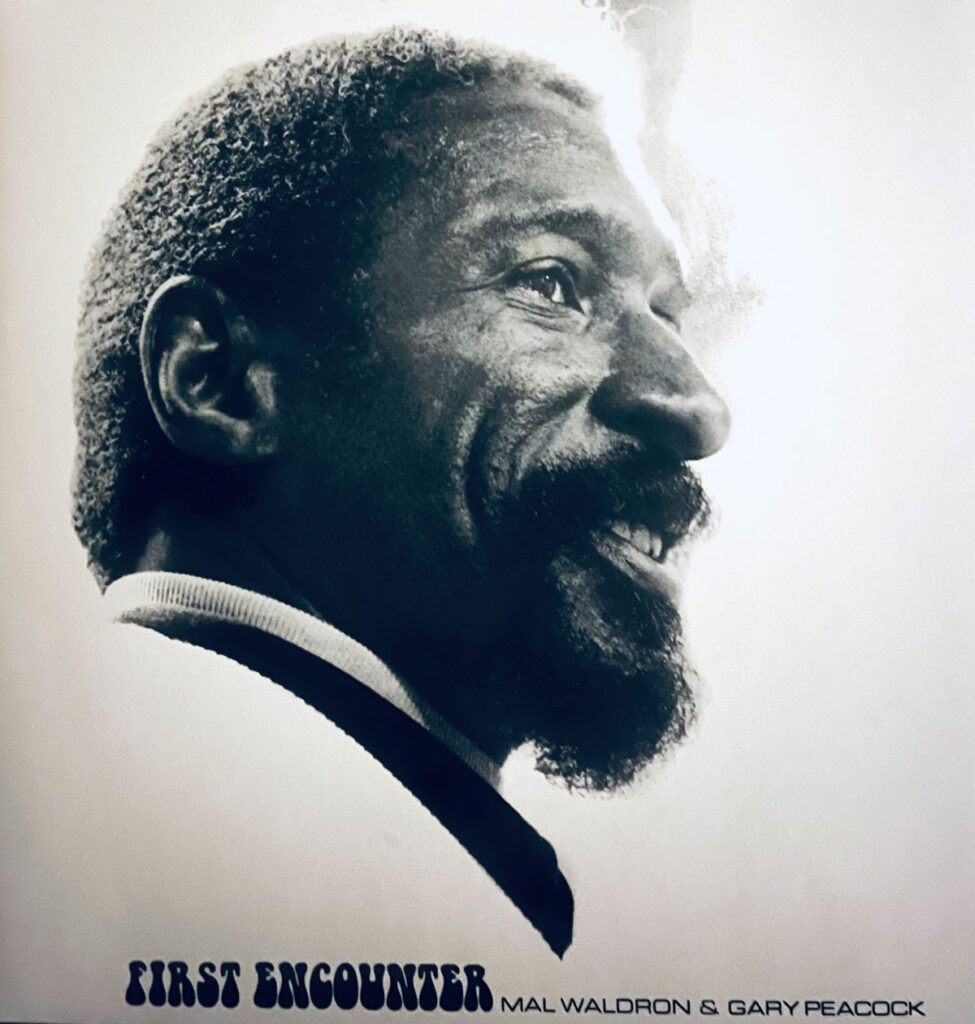

Mal Waldron – First Encounter

The second recommended new release for Waldron’s birthday could be described this way: An American and a European meet in Japan for a recording session and hire the country’s leading drummer. On March 8, 1971, pianist Mal Waldron, bassist Gary Peacock, and drummer Hiroshi Murakami met in Tokyo for a musical session released under the title First Encounter. Both musicians shared a deep interest in improvisational freedom and sonic exploration. The recording documents their interplay in a focused, live session with no post-production editing. First Encounter was made at a time when both Waldron and Peacock were artistically secure and stylistically distinct. The recording highlights both musicians’ individual strengths as well as their clear communicative connection as a duo. The improvisations maintain constant tension, and their interplay feels immediate and free of routine. The album is less a traditional jazz set than a sonic document of three seasoned musicians exploring a shared expressive field. In its reduction and depth, First Encounter offers a concentrated glimpse into the potential of improvised dialogue – marking a special moment within modern jazz. Even if it doesn’t quite reach the exceptional production quality of the Sam Records release, the sheer value of the repertoire alone makes this vinyl a must-have.

And so we say, “Happy Birthday, Mr. Waldron,” hoping that the 100th birthday of this exceptional talent of modern jazz once again brings his work more sharply into focus for music lovers.