Where most people are content to simply plug the headphone jack into the front of their amplifier, dCS recommends building a veritable tower of fully-fledged components specifically for this purpose. I’ve listened to their three arguments – consider me convinced.

Sometimes I ask myself if we’re not going overboard a bit. As I push three cardboard boxes stacked on a hand truck towards the listening room, I can barely believe that I’m really only doing this to listen to music through headphones. But what the heck – taking things to extremes is an integral part of our hobby. And before you ask: no, the headphones aren’t even included. The trio in question is the dCS Lina system, a combination that was primarily developed with headphones in mind, but is of course also suitable as a control center for a stereo setup: The Lina DAC is a network player with digital volume control and can therefore serve as a complete front end of a streaming system in its own right. The fact that the main focus is on solo listening pleasure via headphones can be heard, among other things, in dCS Expanse, an optionally switchable crossfeed optimization that leaves the reverb structure of the recording intact and thus ensures particularly realistic imaging.

What it doesn’t have, however, is a headphone output; the goal here was to translate the technology from the next larger Bartók Apex from its classic standard size into a smaller format. And since the dCS developers are not ones to accept compromises, the headphone amplifier had to be leave the enclosure and now resides in a housing of its own. The third box contains the Lina Master Clock, which, while optional, seems somehow indispensable in this combo. Once everything has been unpacked, the individual components look quite dainty and thankfully can be stacked to form a rather cute little tower that only takes up space on the top rack level.

A Ring for a Ladder

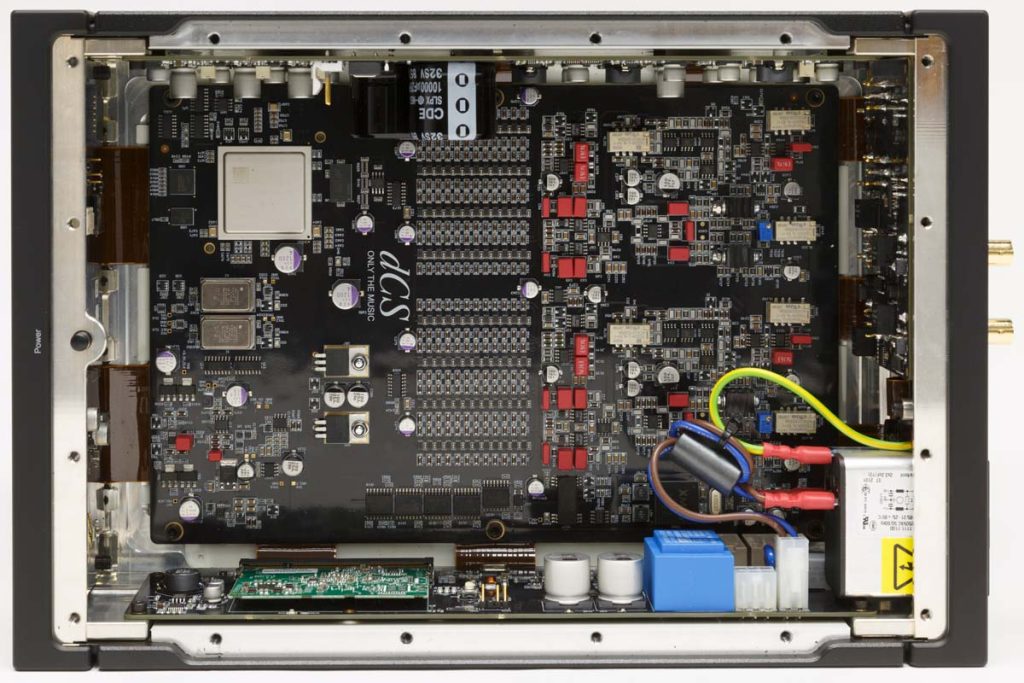

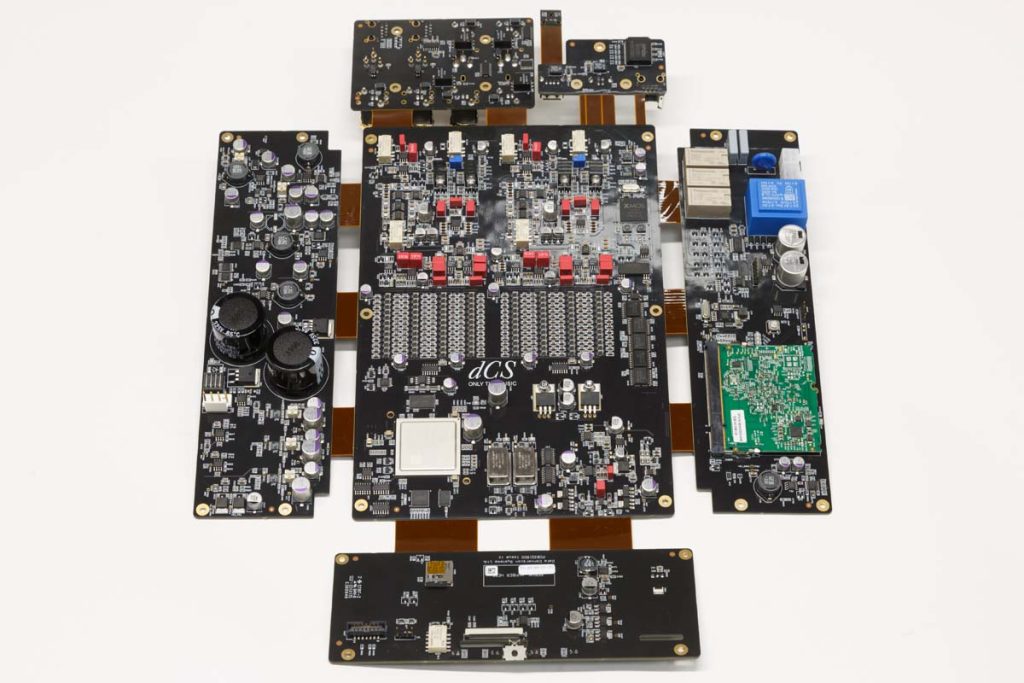

As usual with dCS, the heart of the Lina system is the unique Ring DAC, which superficially resembles a ladder DAC, but takes a different and rather ingenious approach to D/A conversion. One well-known problem with ladder DACs is component consistency – as each of the bits is twice as loud as the previous one, the values of the components must basically remain within unrealistically narrow tolerances: If, for example, the resistance value at the most significant bit deviates from the target by just one percent, the level ends up being off by a greater amount than the full amplitude of the seventh bit. The clever minds behind dCS have come up with a rather ingenious solution to this problem. Firstly, they identified the root of the problem as the fact that each bit has its own current source and therefore feeds the same error into the signal every time it is activated, causing audible linear distortion.

The basic idea behind the ring DAC is that it has a surplus of equal current sources – 48 in all – and uses a clever FPGA-based circuit to assign a different current source to each bit each time it is activated. To make this possible, the signal is first oversampled to 706.4 or 768 kilohertz and then modulated into 5-bit words, which are then run through a mapper at a sample rate between 2.8 and 6 megahertz, depending on the source material. The mapper in turn utilizes clairvoyance and witchcraft to direct the action of the 48 current sources in such a way that the end result is music – at least that’s how I understand it.

In any case, the high sample rate is crucial to the success of the operation: even at 20 kilohertz, each bit is addressed several times and supplied with power by a different component each time, so that the deviations more or less completely average out over time. The signal processing is thus decorrelated from the component constancy, and we obtain an extremely linear and low-noise output signal, which should enable outstanding resolution, dynamics and spatiality, especially at low volumes.

In my role as a user, of course, I don’t have to worry about all the complex signal processing; I’m pleased with the clean navigation via the pleasantly responsive touch display. The Lina DAC is, of course, compatible with all common streaming platforms and also accepts a laptop as a source via USB. I could control the volume via the DAC, but operating the large, silky-smooth control wheel on the Lina headphone amplifier is just so much more fun.

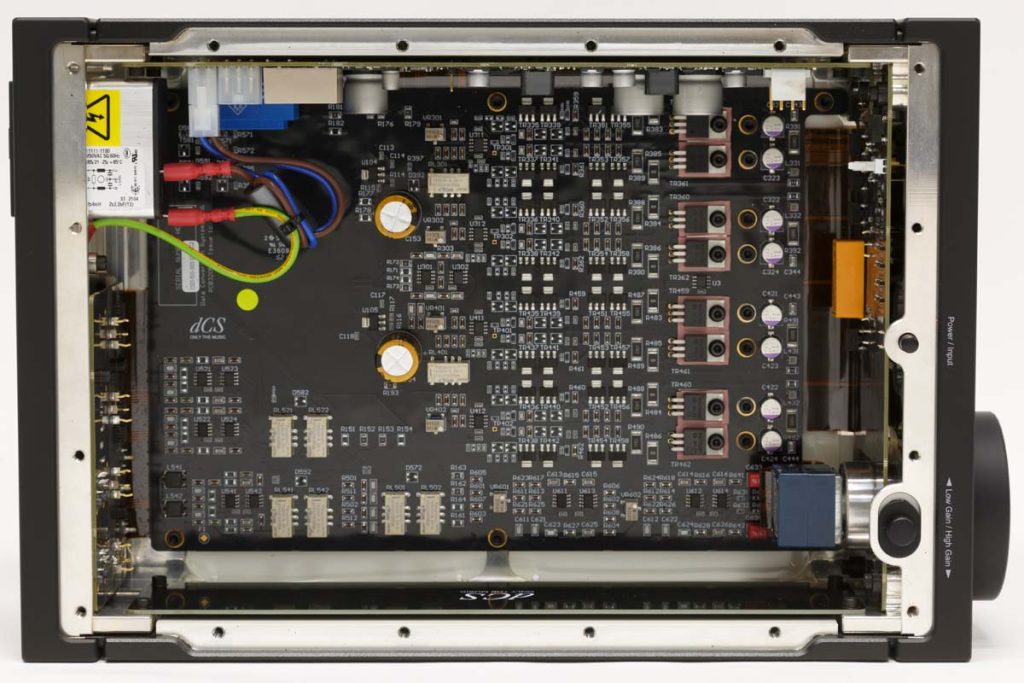

With its inputs for a 6.3 mm jack, XLR and a four-pole balanced input, it will accept pretty much any type of headphones – and it goes way beyond just compatibility: The circuit design, which is called “Class Super AB” in the dCS-Lingo, has been developed with a special focus on the huge range of impedances that prevail among headphones. The dCS developers basically assume that the maximum power in watts is of little significance for headphones – what’s much more important is being able to supply particularly high-impedance headphones with sufficient voltage effortlessly, whereas for models with particularly low impedance current delivering capability is important above all else. This is achieved with a high-bias Class AB design, in which the bias current is controlled by a special circuit designed to keep distortion in check whenever the amp transitions from Class A to Class B mode – if this ever occurs, because in the vast majority of applications the circuit reportedly remains in pure Class A mode. The people at dCS have enough confidence in the performance of the amplifier that they explicitly suggest pairing it with notoriously difficult to drive greats such as the Abyss Diana or the HiFiman Susvara in their marketing material – an amplifier that can drive those can drive anything.

A Worthy Playing Partner

I gave the Lina a go with the Dan Clark Audio Expanse, which not only plays in the right league, but also boasts sensationally low distortion figures thanks to the use of Metamaterial technology, making it a more than suitable test tool for the linearity of the Ring DAC.

I must have listened to Agnes Obel’s “Avenue” (Philharmonics) three times in a row, and even then I still had difficulty describing what I had just heard. Several times I started to jot down notes, only to discard them afterwards because I was constantly finding myself outlining only the character of the recording and not that of the components – until I finally realized that this is a really good sign: Rarely have I heard such a transparent system. The streaming DAC, amplifier and headphones are all so close to the ideal of absolute neutrality that they literally make the sound of the production shine.

By no means does neutral mean featureless, though: incredibly sensitive resolution apart, what is particularly striking about the combination is its ability to reproduce dynamic contrasts even at low levels. The entire Philharmonics album is generally mixed very atmospherically – via the Lina combination this already becomes very apparent at the beginning of the piece, in which Obel is only accompanied by minimal instrumentation. The piece then amps up the intensity in two stages: once when the cello and piano come in, and a second time during the chorus – and what an increase that is with this combination! As wave after wave of intricate sonic density washes over me, I am amazed at how casually the Lina Tower traces the texture of the individual instruments through the heavy, reverb-soaked soundscapes.

To really put the dCS ensemble through its paces, I put on “Really Very Small” by Esperanza Spalding’s Chamber Music Society. On this excellently produced piece that sits somewhere on the axis between jazz and postmodernism, you will look for reverb in vain; the composition and instrumentation alone result in a density of sound that can push even competent systems to their limits and can then sometimes condense into a rather exhausting, indiscriminate buzz. The Lina/Expanse team pulls the strings here with effortless precision and weaves Spalding’s lyric-less vocals with double bass, drums, piano and strings into a dense and delicate carpet in which I can listen to the internal references between the individual players at any time without any effort – at no point do I get the impression that the equipment is facing any challenge at all; I can’t hear any effort in the combination, just a lot of fun at work.

Timing Outsourced

After a while I get curious about the clock’s contribution to the overall performance and unplug it – and I don’t hear any difference, at least not straight away. No big surprise, a DAC of the caliber of a dCS Lina naturally shouldn’t leave anything to be desired. At this point, one could ask why an external clock is necessary at all. James Cook from dCS compares it to a conductor: A good orchestra is capable of delivering an outstanding concert even without the stick-wielding conductor – but only when there is someone at the podium who really knows their stuff can the collection of musicians as a whole perform at their absolute best.

As nice as this comparison is, I take my time to listen back and forth and let my ears alone decide. Gradually, some subtle advantages of outsourcing the clock do indeed emerge: especially in the densest passages, the chain with the master clock keeps a slightly better overview and listening becomes even less strenuous. Clearly, the system works excellently even without the external clock; the pacemaker is the icing on the cake for those who insist on the absolute best – or as an upgrade option for a later date. In a price range where you’re gradually approaching the limit of what is achievable, something like this definitely has a reason to exist.

The beauty of head-fi is that you can build a complete hi-fi system with significantly less money and space. Of course, listening through headphones is completely different to listening through a stereo setup. But who hasn’t wished for a different pair of speakers from time to time – just for a change or to listen to music that the high-resolution gems in the living room don’t really tolerate? Headphones for every day of the week and every musical mood easily fit on a shelf. And this is where the dCS Lina has some major strengths. The system performs at a level that even the very best headphones can fully exploit, and is unconditionally free of any character of its own. If you own several pairs of headphones and appreciate your collection precisely because of the different sound signatures, you can’t go wrong with this combination.

Accompanying Equipment

Variable output network player/DAC: Lumin X1, Soulnote Z-3 | Streamer: Aavik S-580 | CD player: Audio Note CD 3. 1x | Integrated amplifiers: Aavik I-580, Line Magnetic LM-88IA | Power amplifiers: Luxman M-10x, Burmester 216 | Speakers: DALI Epicon 6, Piega MLS 2 Gen2 | Headphones: Dan Clark Audio Expanse, Grado PS500i | Accessories: Finite Elemente Pagode Signature MkII, WestminsterLab cable set

Variable output network player/DAC dCS Lina

Concept: compact streaming DAC with digitally adjustable volume | Inputs: 2 x AES/EBU, 1 x S/PDIF BNC, 1 x S/PDIF RCA, 1 x Toslink, 1 x USB B (PCM and DSD; DSDx2 asynchronous), 1 x USB A for mass storage | Streaming/services: all common ones, including Tidal, Qobuz, Spotify, Deezer and Apple AirPlay 2; Roon ready, UPnP support | Supported formats: PCM up to 24 bit/384 kHz; DSD up to 128, DoP, FLAC, WAV, AIFF, MQA | Special features: Ring DAC with 5-bit word processing, input for external clock | Weight: 7.4 kg | Dimensions (W/H/D): 22/12/34 cm | Warranty period: 5 years | Price: around € 14,750

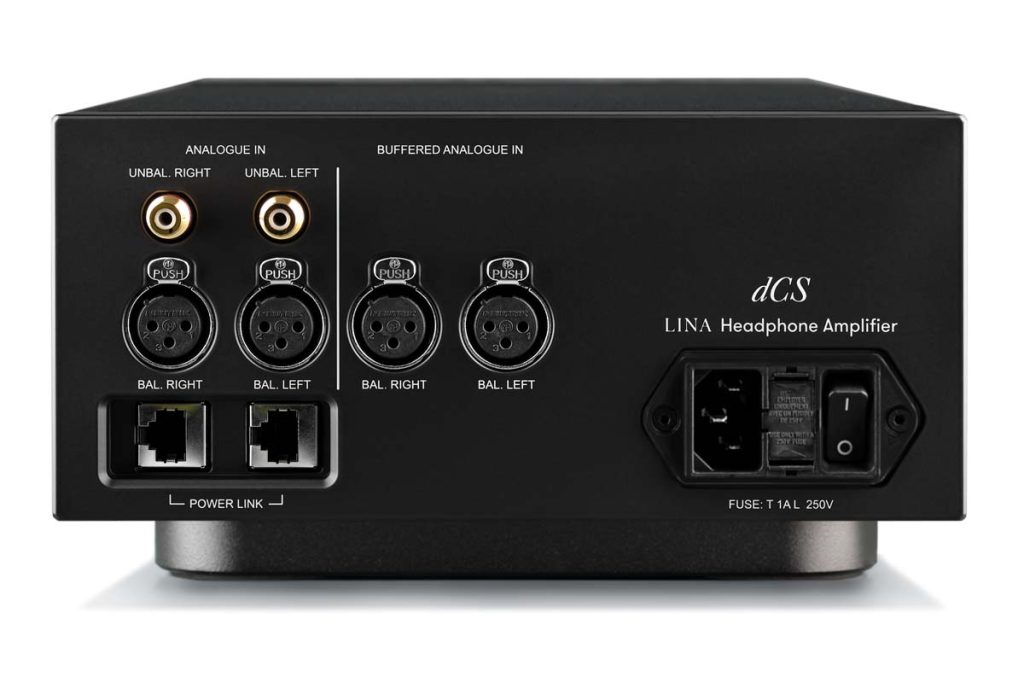

Headphone amplifier dCS Lina

Concept: transistor-based headphone amplifier with “Super-AB” topology | Inputs: 1 x RCA, 1 x XLR unbuffered (16 kΩ), 1 x XLR buffered (96 kΩ) | Outputs: 1 x 3-pin XLR, balanced, 1 x 4-pin XLR, balanced, 1 x 6.3 mm jack | THD+N: < 0.005 % at 1 kHz and 6 V balanced at 30 Ω | Weight: 7.5 kg | Dimensions (W/H/D): 22/12/36 cm | Warranty period: 5 years | Price: around € 10 750

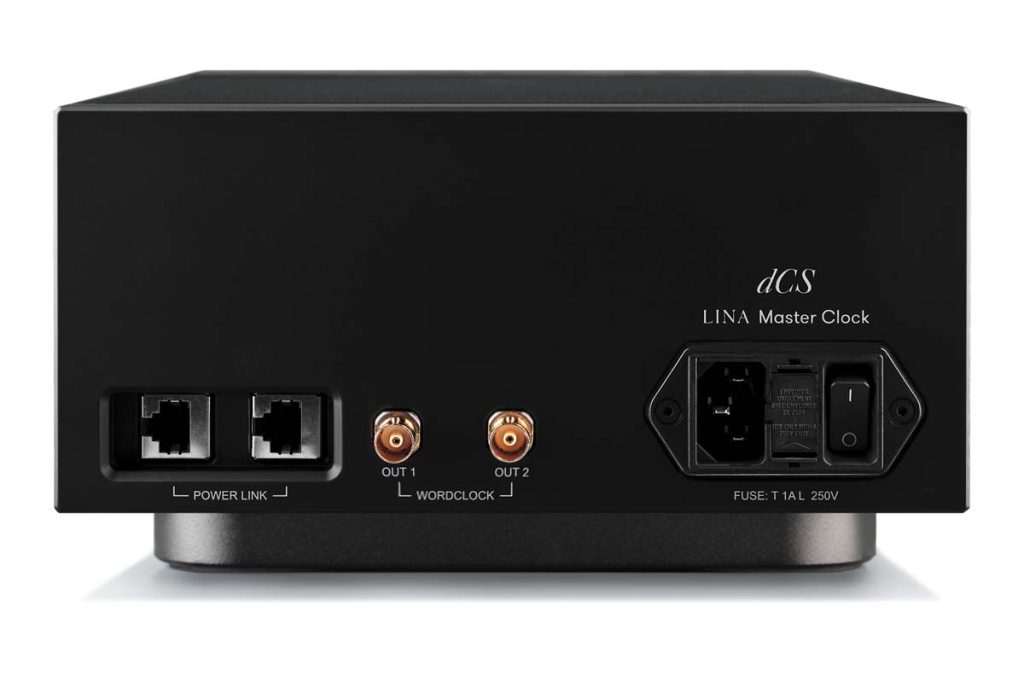

Master clock dCS Lina

Concept: external clock with separate outputs for 44.1 kHz and 48 kHz | Outputs: 1 x BNC for 44.1 kHz (75 Ω), 1 x BNC for 48 kHz (75 Ω) | Accuracy: ± 1 ppm or better | Warm-up time: 10 min to the specified accuracy | Weight: 7 kg | Dimensions (W/H/D): 22/12/34 cm | Warranty period: 5 years | Price: around € 8750

Audio Reference GmbH

Alsterkrugchaussee 435

22335 Hamburg

Phone +49 40 53320359

info@audio-reference.de