First there is this whistling. Perhaps a bird, a tern maybe? Or a member of the Neville Brothers? We don’t know. But these few notes, no matter who whistles them – it’s one of the most beautiful sequences in the world.

They form the intro to what, to my ears, is perhaps the best record ever recorded in New Orleans. Down there on the Mississippi, where the terns nest in the mangrove swamps, where there is a piano or a bongo drum in almost every house and where Malcolm John Michael Rebennack Jr, who died in 2019, saw the light of day. He conquered the world as Dr. John. With delta funk, with voodoo vibes. With his unique style of blues, characterized by Caribbean and Creole grooves and psychedelic sounds.

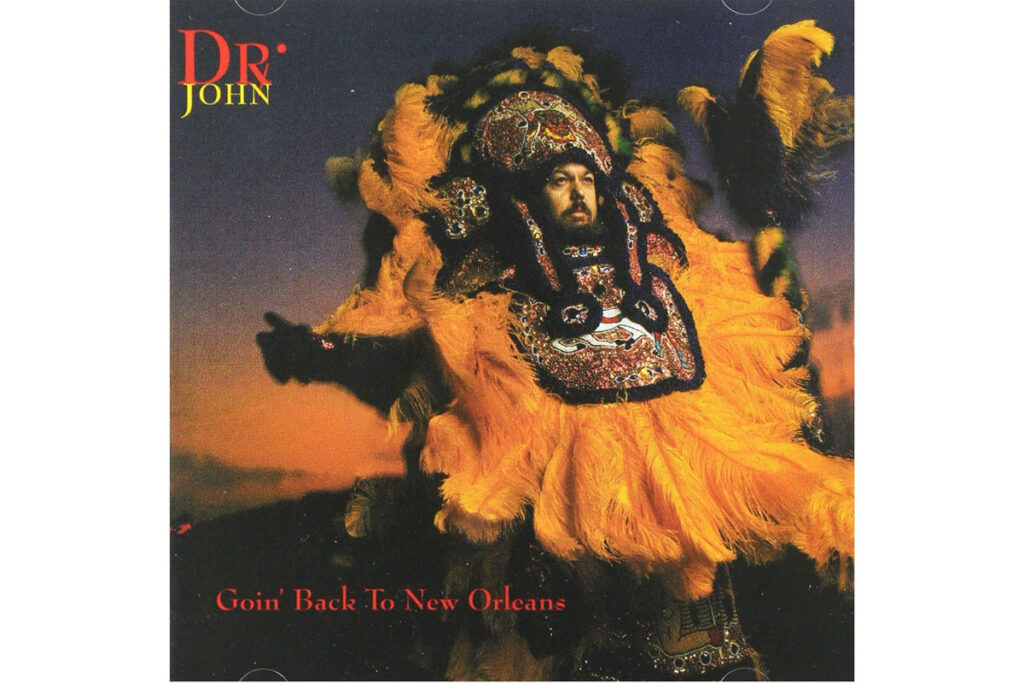

He played with the Rolling Stones and Aretha Franklin. With Lou Reed and Neil Diamond and later with bands such as The Roots and the Black Keys. He recorded anywhere between 50 or 100 records, nobody knows for sure. But never in New Orleans. Trouble with the tax office, as they say. Until spring 1992, when he booked the legendary Ultrasonic Studios, invited around 30 musicians from the Delta and recorded Goin’ Back To New Orleans. “It was time for me to return,” he said in an interview I was allowed to conduct with him as a young journalist.

So the whistled notes, the start of a wild ride through the musical history and culture of New Orleans: “Litanie Des Saints”. A magical, almost fragile and yet pulsatingly grooving opening piece. An exemplary song based on an old children’s song, set to a composition by concert pianist Louis Moreau Gottschalk, a contemporary of Frédéric Chopin, who, before his later fame in Paris, had grown up in New Orleans’ Congo Square to the chants and drum rhythms of slaves who had come from Africa – just like Dr. John.

The Neville Brothers, one of the legendary New Orleans funk groups, sing in French Creole and the rhythm section picks up speed. The whole thing is produced with extreme sensitivity by Stewart Levine. A New York icon who produced one successful album after another for Simply Red, Joe Cocker and Huey Lewis. He was also the head of the musical program for the “Rumble in The Jungle” boxing match in Zaire between Muhammad Ali and George Foreman – also known from the documentary film When We Were Kings – and had become one of the most sought-after music producers of his time. In the spring of 1992, in the studios on the Mississippi, he achieved the feat of allowing almost three dozen musicians, including 15 wind players alone, to let off steam with passion. And in the end, he manages to arrange, harmonize and balance every note, every slightly sluggish offbeat, to create an audiophile masterpiece.

All the other songs … I could write a doctoral thesis on each of them. There’s the sad duet of trumpet and Dr. John’s piano in “I Thought I Heard Buddy Bolden Say” by jazz pianist Jelly Roll Morton. There is the Dixieland classic “Basin Street Blues”, first recorded by Louis Armstrong in 1928 and subtly funked up here. Then there’s “Do You Call That A Buddy” by songwriter Don Raye, which is brought up to speed with slap bass and horns. And the bitterly angry “How Come My Dog Don’t Bark (When You Come Around)” by the now forgotten Prince Partridge, here transformed into a pulsating funk in typical Dr. John style. Archetypal blues, fat funk, emotional soul – Goin’ Back To New Orleans is the perfect work to test high-end equipment for versatility and sensitivity. It also won a Grammy, albeit in the “Best Traditional Blues Album” category, which doesn’t even begin to take into account the breadth of the songs. What did Dr. John himself once say? Anyone who doesn’t have fun with this music is probably already in the box, “ready to put down six feet in the ground…”

Dr. John – Goin’ Back To New Orleans

Label: Warner Music

Format: CD, LP, DL 16/44

Find Dr. John – Goin’ Back To New Orleans on discogs.com