As a child, Federico Albanese went to La Scala in Milan every Sunday, played bass in a punk band as a teenager, and later married Ludovico Einaudi’s daughter. Today, he is himself an acclaimed pianist who plays in opera houses and at music festivals around the world. In conversation with FIDELITY, Albanese reveals how the sunlight in Piedmont and James Joyce’s Ulysses influenced his new album Blackbirds And The Sun Of October.

Federico Albanese is late. The video call window remains black at first. A record manager has to call him, then his dark curly head appears on the screen. He apologizes, saying he lost track of time while practicing the piano. He is currently in the midst of preparations for his new tour, on which he will now play the songs from his new album Blackbirds And The Sun Of October for the first time. It is his first new solo program in three years, and practicing is “hard, hard work,” he says, looking tired but friendly: “You get used to certain soundscapes too quickly. The trick is to keep reinventing yourself. But now to us: What would you like to know?”

FIDELITY: Federico, first a confession. When I was offered the interview with you, I didn’t know you. Knowledge gap.

Federico Albanese: That happens.

Of course, I’ve filled that gap in the meantime. Even my daughter listens to Albanese now. The title track of your new album has earned a place on her “Do not disturb, I’m in the bathroom for two hours” playlist. Not everyone can do that.

That’s wonderful! Music is so important. How old is your daughter?

She just turned 18. Her sister is 15 and is currently going through her ABBA phase.

Oh, I see… I’m a father of three myself, but my oldest is only 8, my daughter is 5, and my youngest is just 9 months old. Fortunately, we don’t have two hours in the bathroom yet. I have other issues… (laughs)

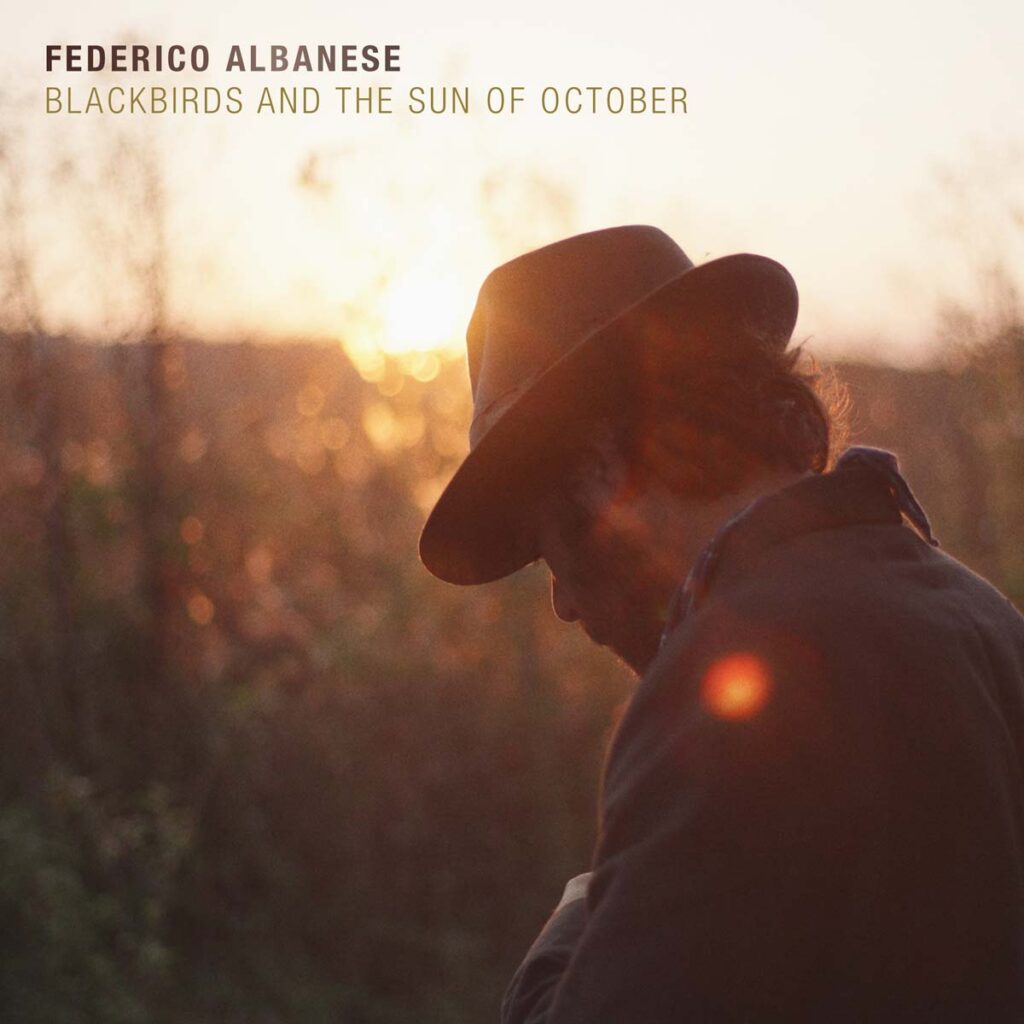

Federico, it’s not often that the cover artwork and the first song on an album go so perfectly hand in hand. “Into The Sun” sounds just like the picture looks. So which came first: the sound or the sun in the photo?

The cover image came later. It was created during a video production for the album. For me, the image perfectly captures the mood in which the album was created. At the end of 2022, after several years in Berlin, I moved back to Italy with my family, to Piedmont, to a house in the countryside. The colors, the landscape, the sun captivated me. The light in autumn, when the year is drawing to a close, is something very special. Magical. That was the beginning of the album.

From “Into The Sun,” I can’t tell whether the sun is rising or setting. Is it the dawn of a new day for you, or is it a look back?

The rising sun. We were just talking about our children. One of my fatherhood themes is getting up early. We start at 6 a.m. at the latest, every day. It’s cruel, but also beautiful. That’s how I experience the sunrise. The incomparable light on rolling hills. In Berlin, where we lived for a few years, you look out the window and see only other people looking out of windows. Walls, stones, buildings.

The album sounds very joyful, like the rhythm-driven title track. Some of your previous albums sounded more minor than major.

Good observation. Yes, this album is bright, it’s focused on life. Much of what I composed before was a deep-sea dive into inner worlds. Into previously closed rooms of my self.

The second song, “Ulysses,” refers to a work of literature that is as big as the sun. A work of art in which words, thoughts, and fragments of memory are sometimes raw and seemingly confused—James Joyce’s famous stream of consciousness.

I read Ulysses not too long ago. I find it fascinating that everything described in it—the book is a thousand pages long, after all—takes place in a single day. You are right there in people’s heads as they think, as they fear, as they rejoice. I am also live inside my own head when I compose and the set pieces, ideas, discarded fragments, and who knows what else fly around.

The result doesn’t show this: the notes seem to be in the right place, the whole thing seems very homogeneous.

This has to do with the other, personal level of meaning. “Ulysses” also plays with the Odyssey, with Greek mythology. In fact, Blackbirds is the first album I composed and recorded entirely in my home country, Italy. My return to my roots after a long journey. My time in Berlin was important. But I’ll never speak German well, the culture is different… I only really found myself with this album.

Another song is called “A Story Yet To Be Told.” Can stories be told through instrumental music?

Of course! It’s all about our imagination. The power of imagination. That’s the beauty of instrumental music. It’s extremely subjective. In the sense of what associations the artist has when composing and what the listeners think about it. It’s about creating space. Space for feelings, for thoughts, space simply for being. The greatest art is to write music that can do that. That expresses a lot with just a few notes. That also allows for silence.

“Bloom,” on the other hand, sounds dramatic. In a movie, I would expect the hero to appear for the first time now.

I had been carrying the melody and rhythm around with me for quite some time. That dynamic, dramatic da-dada, da-dada that you surely mean. In fact, the piece first took on sharper contours when I was involved in a different context with a story featuring knights. In that respect, I can understand your association with the hero, interesting.

Let’s take a quick look back: it is said that a music teacher once said to your mother, “This boy has potential.” You were two or three years old…

My mother’s favorite story. She thinks she was the one who got me to study music. On the advice of this very man, who wasn’t even a teacher—I wasn’t even in school yet—but a salesman in a music store in Milan.

Your mother still sent you to piano lessons every day from the age of six.

I hated it. I didn’t want to go. That was in the 1980s. We talked about our children at the beginning, Philip. We are different fathers today; it’s a different time. My mother said at the time: You’re going there. End of discussion. She wouldn’t have accepted a “No, I don’t want to.” At home, the rule was: You eat what’s on the table. And you go to music lessons. It was a kind of preparatory training for music boarding school. Fortunately, I didn’t have to go there; my parents sent me to a normal public school. I probably would have been well trained at the conservatory, but it would have been very strict and rigorous. I certainly wouldn’t have the freedom today to make the music I make.

Interesting.

Strict training isn’t always a good thing. I don’t see myself as a pianist, which I would certainly have become if I had chosen the other path early on. Today, I am a composer, instrumentalist, performer, and, yes, also a bit of a pianist.

You play the piano in the sold-out Elbphilharmonie, but neither Chopin nor Mozart; you play at the Montreux Jazz Festival, but not like Oscar Peterson. What does your mother say about that?

Oh, she’s extremely happy and proud. After all, she’s responsible for it… (laughs) Seriously, if she hadn’t pushed me so hard, I wouldn’t be where I am today. You mention all the big names. You know, when you’re young, you copy your role models. I went through a phase where I wanted to sound like Nirvana, then like Queens of the Stone Age. As you get older, you gain more and more of your own experiences. You experience life. And things arise within you, emotions, repressed feelings, beautiful things, whatever. And if you’re lucky and hard-working, you find your own voice.

On the way there, you didn’t just copy Nirvana, you also played bass in a punk band.

My father loved rock music, my mother loved classical music. On Sundays, for example, I would go to La Scala with my mother. Not to the evening performance, but to the opera rehearsals in the afternoon, which were free and open to the public. And a few days later, I would go with my father to a Green Day concert. Both sides have shaped me to this day. Classical music and rock ‘n’ roll. You may not hear it right away, but that attitude of “not thinking,” that immediate “in your face” quality of rock music, even more so of punk, and the creativity of prog rock—all of that is in my system. Ultimately, I write rock songs. They just don’t sound like it.

Federico Albanese

Federico Albanese is one of the most important pianists of our time, whose work cannot be classified in any classical genre. In his music, he combines classical, electronic, and ambient elements to create very melodious, often minimalist soundscapes. His new fifth studio album, Blackbirds And The Sun Of October, is a good example of this. Born in Milan in 1982, the artist has performed at the Elbphilharmonie in Hamburg, the Montreux Jazz Festival, and the influential South by Southwest Festival in Texas. In the 2000s, he founded the avant-garde duo La Blanche Alchimie together with singer Jessica Einaudi, daughter of pianist Ludovico Einaudi and now mother of his three children. In addition to his solo albums, Albanese has also made a name for himself as a film composer, most recently writing the soundtrack for Last Swim, a youth film that won an award at the 74th Berlinale in 2024.