What music lover doesn’t know those famous opening words to US3’s 1992 jazz-rap classic Cantaloop (Flip Fantasia): “Ladies and gentlemen, as you know we have something special down here at Birdland this evening, a recording for Blue Note Records.”

That announcement came from a live recording of the Art Blakey Quintet in February 1954, captured at New York’s hottest jazz hotspot of the time: Birdland. As the club’s emcee, Pee Wee Marquette, proudly declared, it was a big deal that Blue Note recorded a live concert right there on the corner of Broadway and 52nd Street—an honor that in later years was reserved almost exclusively for the rival Village Vanguard. That recording was later released as Art Blakey – A Night at Birdland Vol. 1 on a ten-inch LP.

A Wild Melting Pot

Before we look at today’s Birdland, it’s worth revisiting the club’s storied—if often turbulent—past, a history full of breaks, scandals, and long silences (quite unlike the continuous legacy of the Village Vanguard). When Charlie “Yardbird” Parker rose to stardom as a bebop pioneer in the late 1940s, entrepreneurs Morris Levy and Oscar Goodstein saw their chance: they acquired a basement space near Broadway and 52nd Street, right in the thick of the theater and nightclub district, and named it after Parker’s nickname—Birdland.

Licensing issues delayed the opening, but on December 15, 1949, the doors finally opened with a program titled A Journey Through Jazz, featuring Parker himself, Stan Getz, and Harry Belafonte. Ironically, Parker rarely performed there—not, as many assume, because of his drug problems, but, as manager Goodstein put it, because he “always wanted money.” Still, his name became forever tied to the club.

Birdland wasn’t just a venue—it was a magnet and a stage locked in constant rivalry with the Village Vanguard to present the hottest acts. Dizzy Gillespie, Miles Davis, Thelonious Monk, Bud Powell, John Coltrane—all played there. Count Basie’s orchestra appeared regularly, and George Shearing immortalized the club with his standard Lullaby of Birdland, one of the most famous jazz compositions of the 20th century. Decades later, Weather Report paid homage with their hit Birdland, later covered by Quincy Jones, The Manhattan Transfer, and many others.

Some of the most legendary live albums in jazz history were recorded there, including Blakey’s A Night at Birdland and Coltrane’s Live at Birdland. Celebrities outside the jazz world—Frank Sinatra, Marlon Brando—also mingled in the audience. With roughly 500 seats, ranging from elegant boxes to folding chairs crammed next to the bandstand, Birdland was far larger than the Vanguard. Teenagers were even admitted, though without alcohol.

The eccentric master of ceremonies, Pee Wee Marquette, became notorious for deliberately mispronouncing musicians’ names unless he was tipped—his nasal, androgynous voice turning the trick into high comedy. Some claimed a chunk of the audience came just to see him. But the glamour had a dark side: in 1959, cofounder Irving Levy was stabbed to death inside the club—apparently unnoticed by patrons. That same year, Miles Davis was brutally beaten by a police officer outside the entrance.

By the early 1960s, jazz was losing mass appeal. Birdland slipped into financial trouble, filed for bankruptcy in 1964, and closed a year later. New owner Lloyd Price reopened it as an R&B spot called the Turntable. The original Birdland was gone.

Mainstream Comeback

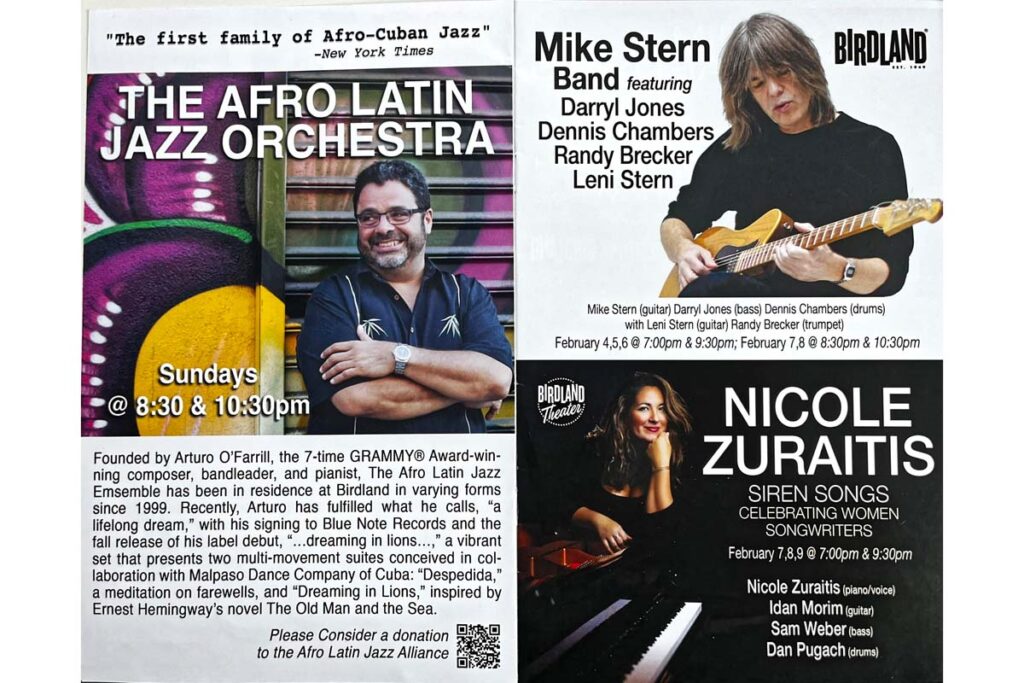

Birdland was reborn in 1985, first on the Upper West Side in a smaller space that tried to showcase Harlem-based musicians. In 1996, the club finally found a permanent home in the Theater District on West 44th Street. The new owner, John R. Valenti, revived the old traditions while spotlighting commercially successful mainstream jazz stars like Diana Krall, Michael Brecker, and Pat Metheny.

Today, a visit to Birdland means braving the tourist chaos of Times Square, both coming and going—not exactly ideal if you want a relaxed meal before or after the show. But inside, the crowd is surprisingly untouristy, even pleasantly jazz-nerdy. Still, it’s obvious that jazz is no longer a mass-market draw in New York; the long lines are all outside the nearby Broadway musicals.

Birdland has kept the original “dinner and show” tradition. There’s bar seating, but the best spots by the stage are reserved for dinner guests. On a typical Friday at the 7:30 p.m. set, the audience is a colorful mix: hoodie-and-beanie jazz nerds, Upper West Side lawyer couples, Wall Street banker bros, scattered tourists, and birthday groups. Some are clearly there for Mike Stern and Michael Brecker, while others mainly came for dinner and treat the concert as a bonus.

Either way, few leave disappointed. The menu offers pasta, burgers, and vegetarian options—solid quality at fair prices for Manhattan. Importantly, the music never fades into background noise: the staff is friendly, efficient, and discreet, ensuring the show runs smoothly. For the best seats up front, book early and arrive on time. Hardcore fans even get to watch the musicians set up the stage and snap the first photos of the night. Despite a sometimes upscale crowd, the vibe isn’t stiff—being so close to the band allows for a near face-to-face connection. By the end, even the lawyer’s wife in her chic suit is cheering and whistling for an encore. But with the second set scheduled barely an hour later, encores rarely stretch beyond a single tune.

A Tough Choice

Birdland or Village Vanguard? That’s the eternal question for jazz lovers visiting Manhattan—especially if there’s only time for one show. The answer depends on your perspective. Personally, I lean toward the Vanguard—for the authenticity of its uninterrupted decades-long history in the same basement space, and because it’s still a family-run business, now in the capable hands of Deborah Gordon.

Birdland, by contrast, trades more on the glow of its name and offers a broader overall package. It reaches beyond hardcore jazz fans, complete with a merchandise stand. It still bills itself as the “Jazz Corner of the World,” though the self-designation carries a touch of arrogance. The Vanguard, meanwhile, remains pure jazz.

But truthfully, the real point is to hear the music, not to worry about which club you choose. So relax, check out the programs, and go with the one that excites you most. And if you’re adventurous enough to explore how jazz and avant-garde are fusing in today’s Manhattan, you’ll probably head to (Le) Poisson Rouge anyway. But that’s a story for another issue of FIDELITY.

Birdland

315 W 44th St, New York

NY 10036, USA