At times, I envy my English-speaking colleagues. They can break a phenomenon down to a single word and everyone understands what they mean. In German, we often need what feels like a book chapter to make comparable statements. One term that kept buzzing through my head when I visited Wilson Benesch in Sheffield was “mindblowing”. The German translation “overwhelming” doesn’t hit quite like that. And let’s not even try translating it literally to “gehirnblasend”. Although … now that I read it in black and white – it actually fits the bill quite well!

Our three-day press trip to England can serve as evidence that there’s no substitute for being there in person. Don’t worry, this is not intended as an advertisement for more exciting press appointments. I’m talking about very practical aspects: If you ask the Milnes family for information about their speakers, you’ll get it – tons of it. I could fill an exercise book with the material they provided for the test of the Resolution 3Zero (FIDELITY No. 66) alone. I bravely made my way through most of it and – I’ll be honest – understood about half of it. What stuck with me is that Wilson Benesch somehow managed to become part of the pan-European SSUCHY project. This gave the manufacturer access to research and production capacities that other loudspeaker developers can’t even dream of. The concentrated know-how is also evident in the extraordinary products. However, I could only guess what SSUCHY is all about, why and by whom it is run and, above all, why a loudspeaker manufacturer of all things became part of this exclusive club.

So let’s jump straight to the second day of our visit to England. We had the opportunity to take a tour of the halls of the AMRC (Advanced Manufacturing Research Center). The University of Sheffield is part of the SSUCHY project and conducts materials research on its behalf. However, the goal is not simply to develop a smorgasbord of high-tech ingredients. These materials should have a practical relevance or purpose, be scalable for industrial scale production and be able to be completely dismantled and recycled at the end of their life cycle – Europe wanted to become more independent back in the late 1990s. I deliberately avoid mentioning the EU here, because from a Sheffield perspective … the topic causes a slight headache.

We were not allowed to take photos at the AMRC, otherwise I could show you that they are working on the next generation of Rolls-Royce engines. The task is to save material and still achieve greater stability. In fact, this also has to do with resonances – both inside and outside the material. In the entrance area of the laboratory, the high-pressure turbine housing of a jet engine serves as a nerdy base for a side table. The component is milled from a block of aluminum, Craig Milnes explains to me, and in the past the percentage of production rejects was enormous. The AMRC realized that as the thickness of the material decreases, the speed of the milling machine gets closer and closer to the natural resonance of the component. If the two coincide, things can become unpleasant. Once this pitfall was discovered, the AMRC developed software that modulates the speed of the milling head and adapts it to the requirements – with resounding success and considerable cost savings. I also discover the cute model of an Airbus A350. The lab found a way to lighten the landing gear’s hydraulic dampers by around 200 kilograms. There are six of these pistons in each machine, so the savings add up to 1.2 tons. Meanwhile, mini-reactors for submarines are being developed in building compounds that we were not even allowed to enter for obvious reasons.

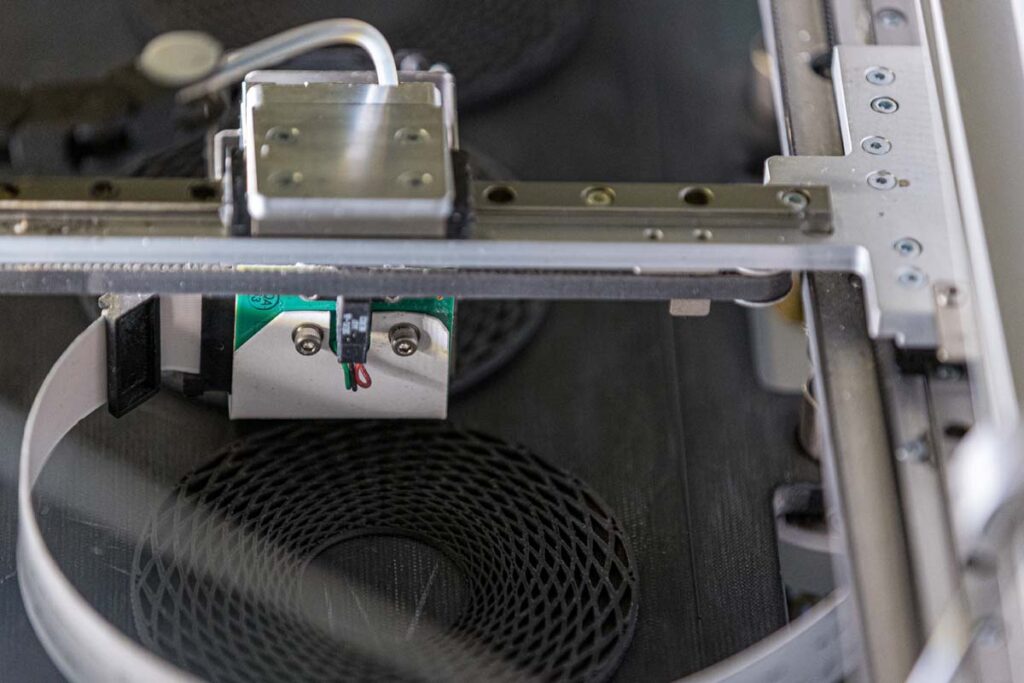

As a consolation, we got to see how carbon weaving machines are assembled in several shielded chambers. Carbon mats consist of wafer-thin flat ribbons that (at least visually) resemble the tape of an audio cassette. The largest of these “looms” is loaded with hundreds of tapes of different widths and thicknesses. It takes a good month until everything is adjusted and in place, we are told. Once this is done, you absolutely do not want any of the ribbons break under any circumstances. If everything works, the huge apparatus spits out carbon meshes of a complexity that no human could wrap his brain around. During our tour, we saw propeller and turbine blades, spoilers, monocoques and tanks from racing cars as well as more mundane products such as snowboards and – drumroll – Wilson Benesch housing components, all of which were “baked” seamlessly and crease-free from such carbon mats.

It started to dawn on me what business Craig Milnes’ company had in the SSUCHY project: Research at this level, the lab staff explained to us, can only succeed if the right questions are asked right at the start. The aim is to refine processes and improve the materials used. To this end, they were looking for manufacturers who had experience in working with such ingredients and wanted to develop their skills further (also for their own benefit) – by asking the tinkerers and researchers the right questions and occasionally coming up with completely new, often out-of-the-box ideas. A win-win situation: companies like Wilson Benesch gain access to unique technologies, and the SSUCHY initiators benefit from manufacturing processes that, along with Airbus innovations, could one day lead a to fully compostable Eurofighter 2 – or something of that sort.

Craig Milnes explained to me during our tour that he had to apply for projects. Such a proposal comprises several pages of sketches, functional descriptions and formulas. Many of these have already been realized, but he has also had deal with the experience of being rejected by the AMRC, which was recently the case. However, he has learned to view such setbacks as an incentive – he will make a new attempt in spring. Meanwhile, such setbacks do not diminish the appreciation of Wilson Benesch in the slightest: Milnes’ understanding of the function of his components, of resonances and of the use of state-of-the-art composite materials was already so advanced at the end of the nineties that a conglomerate of highly decorated universities came to the conclusion: “We can learn something from them.” But that’s enough SSUCHY for now.

Sheffield is a city of bricks. Exciting and dynamic: the aging industrial location has succeeded in transforming itself into a university and high-tech location. Collieries and foundries once stretched far into the city center. Today, the complexes are home to service providers, businesses, museums and some pretty darn interesting pubs. As befits such a location, Wilson Benesch is also a guest in an old industrial building on the north-western edge of the metropolis. Peas were once processed into puree tablets here. During the Second World War, the company was temporarily nationalized and its capacity expanded at lightning speed. After doing its bit to supply the island – thank you for your patriotic efforts – the machines were so run down that the owners had to declare bankruptcy. One man’s sorrow is another man’s joy: Craig and Christina Milnes were able to get a good deal on the building, which was somewhat run down after decades of vacancy.

The interior of the company headquarters symbolizes Wilson Benesch’s introduction of state-of-the-art technologies into market with a sense of tradition. The exterior façades, room layout and the excellently aged wooden floors bear witness to the building’s original condition and could tell stories. The Milnes were particularly taken with the large windows. Daylight was needed above all else for the selection of fine veneers. Here and there you can still discover archaic lathes and historic-looking milling colossi. The wood workshop with its calm atmosphere, veneer storage, glue tins and gracefully aged workbenches looks as if it has been snatched from a documentary about “good old” artisanry. Just a few doors down are computer-controlled metal milling machines and other high-tech workbenches. In another room, a noisy armada of 3D printers is busy working on components for the Fibonacci loudspeakers. On a table directly opposite is a high-performance laser that carves lettering into metal components at an incomprehensible speed, leaving behind small clouds of aluminum oxide. In one of the larger workrooms, some of the employees are busy marrying individual parts to form the distinctive drivers of the Wilson-Benesch loudspeakers. Precision work that requires a trained eye. It is only on this occasion that I realize that each chassis is tuned to its specific task and labeled accordingly. I don’t want to dwell on the details here. If you would like to learn more about the construction and function of a Wilson Benesch, we recommend the review of the Resolution 3Zero, which you can find free of charge and in color HERE. Another thing that amazes and impresses me is that WB really does manufacture every aspect of its speakers in-house – only the amplifiers for the subwoofers and individual crossover parts are bought in.

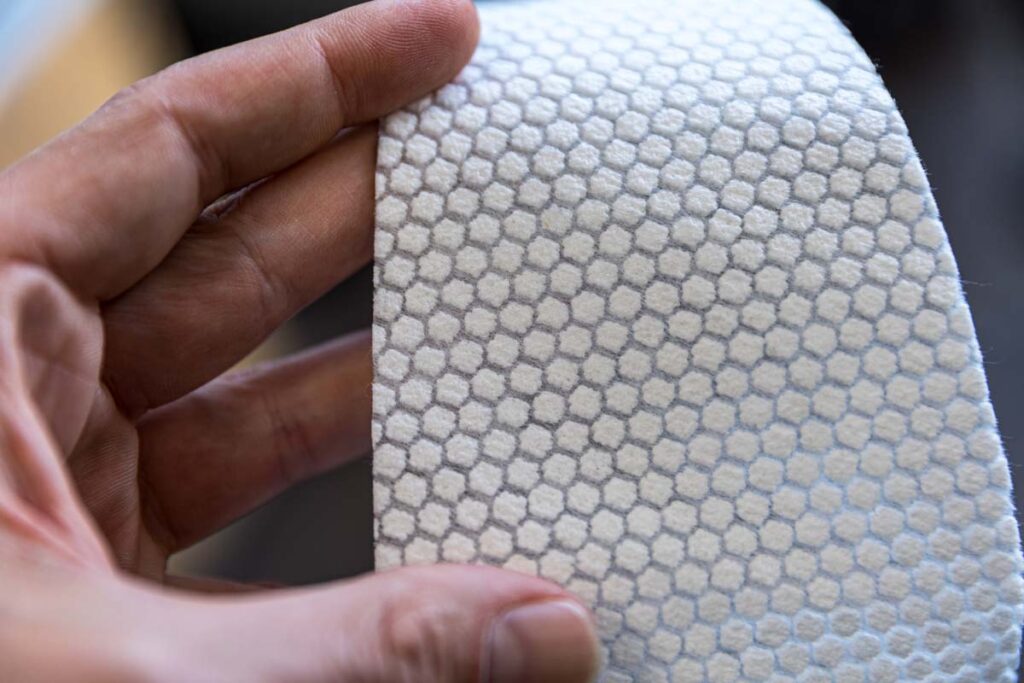

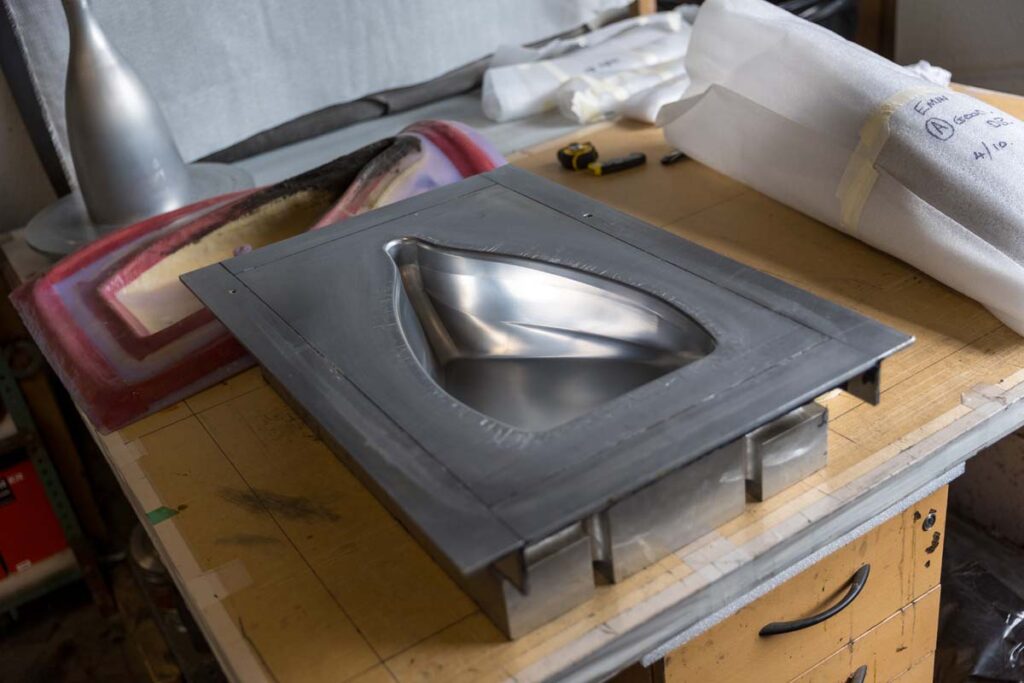

We now continue across the courtyard to a separate building housing the enclosure production facility. The “sound bodies” of the loudspeakers are made of a bio-composite: One layer each of cork, flax fabric and a type of rubber granulate are cast in epoxy resin under high pressure. It took years to fine-tune the process so that no bubbles form when the material hardens. An opaque phalanx of wires and hoses covering good parts of the machine ensures this. Back in the main building, I then experience a benefit of AMRC research in a vivid way: Craig Milnes asks me to embed a carbon mat in one of the molds for the head plates of the Fibonacci loudspeakers. As I am desperately trying to get this right, the quiet giggling behind my back gives me an inkling that I’ve been given an impossible task. Shortly afterwards, Milnes hands me another piece of fabric with a noticeably different structure and a white coating on the inside. I place the mat in the mold and it slides into the curves as if by magic. The looms at the AMRC build up the material in such a way that it becomes malleable and, to a certain extent, stretchable. A roll of this magical material costs Wilson Benesch a cool 15,000 euros.

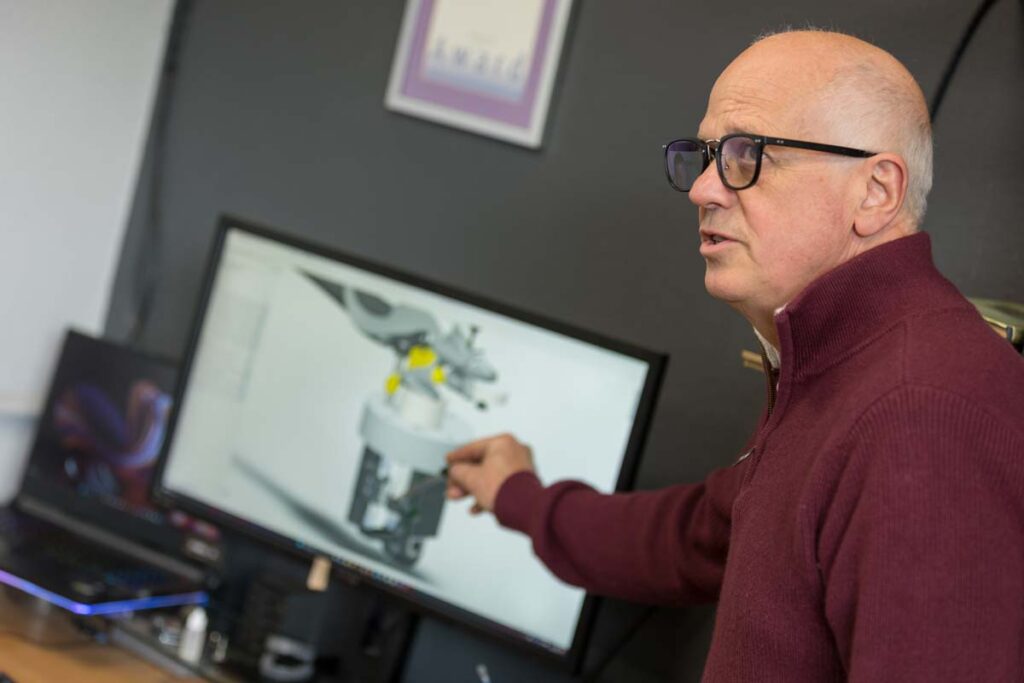

With that, we end our tour and find ourselves in the company’s impressive listening room. During the pandemic, there was finally an opportunity to transform the former management offices into an excellent-sounding room within a room. Our attention, however, is not on the sublime Eminence, which stands here ready to play, but on a table at the opposite end of the room. Craig Milnes has prepared some details of his lifeblood project for us. In fact, the nucleus of Wilson Benesch lies in a record player that the managing director put on ice in the early nineties in favor of his loudspeakers. In the meantime – he took up the project again years ago – the analog statement has been finished.

Absolutely nothing about this turntable is ordinary: the organically shaped carbon tonearm rests in a single-point mount; to ensure that the thin signal conductors do not have even the slightest influence on the balance, they exit the arm exactly at the center of gravity at the top. Because he couldn’t find a suitable motor, Craig Milnes simply converted the entire platter into a giant direct drive. The coils for this are wound directly in-house. He also devised a magnetic gearbox that runs so smoothly that I can hardly keep my hands off it. Instead of a chassis, the tireless sound researcher ended up developing a complete rack system in which the turntable is anchored. This work of art, which is estimated to cost “somewhere around 200,000 euros”, will not be exported to Germany. If you are interested, please contact the sales department (see below).

They will be able to put you in touch. For us, the turntable underlined the manufacturer’s expertise above all: the exhibits on the table showed that Milnes stimulated a large number of studies and experiments on the way to the finished product: for example, there was a feather-light “wheel” with three spokes, which consists of a filigree hexagonal metal structure that cannot be twisted or bent even when force is applied. Meanwhile, an arrangement of different models proved that the tonearm had gone through a maturing process of more than 30 years. I could go on and on with the list of my discoveries and observations, because what I’ve told you so far only scratches the surface. As a shortcut, let’s just say that Wilson Benesch is one of the 0.1 percent of hi-fi manufacturers who can rightly say that they combine music reproduction with rocket science and that there are still many ideas lurking in Craig Milnes’ head waiting to be realized. As promised at the beginning: absolutely “gehirnblasend”!

IAD

Johann-Georg-Halske-Straße 11

41352 Korschenbroich

Phone +49 2161 617830

info@iad-gmbh.de